Doubt, uncertainty, and questioning things are considered hallmarks in philosophy. Not being certain in a belief is considered a virtue due to how often we are mistaken.

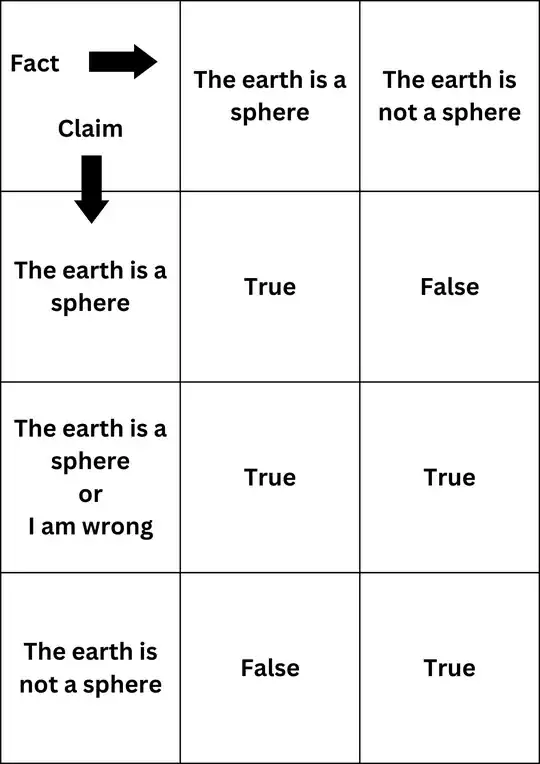

But philosophy is also associated with finding out the truth about things. However, being uncertain implies having a probabilistic form of belief that doesn’t seem to exist in reality for many things. For example, ghosts are either real or not. The earth is either a sphere or not. With these kinds of things, reality is binary. When it comes to matters of existence, there are no grey areas. As such, why is it sensible to leave even a bit of a doubt in your beliefs about these matters?

If a rational belief is one that amounts to having a belief that is both justified and is true, how can it be rational to even say “I think the earth is most likely a sphere but I could be wrong.”

If the earth is a sphere, then wouldn’t you ultimately be wrong for even thinking that it’s a possibility that the earth isn’t a sphere? If it’s not a sphere, you would also be wrong.

Being uncertain seems to make your belief wrong either way. Being certain atleast seems to make your belief correct if you turn out to be right. Why is the former then considered more rational?