I distinguish between "free will" and "freedom of action".

Free will: A person at a situation A can decide between action B, C, D. He choses B but could have acted differently.

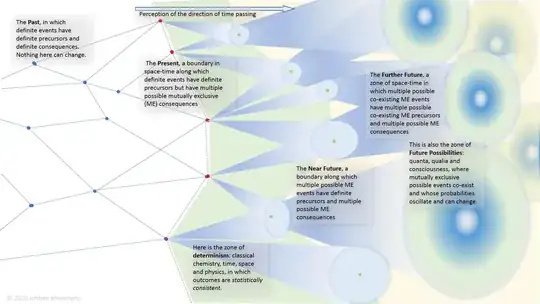

Under the assumption that our decision-making process is not dependent on randomness this is not compatible with a physical world.

All accounts of "I could have acted differently" only work in retrospect. If you are in a situation like A but not A, let's call it situation A', you have gained new knowledge that you never had in a situation A and you were in a different state of mind. Hence making it possible to react differently. Yet still the way you act is a necessity. Deterministic.

Freedom of action:

Given a certain situation A a person has multiple options, B, C, D and can decide which to take, without people or circumstances forcing them to take or denying them certain choices.

This is compatible with a physical world as it only takes into account if they can actualize their desire. Viewed in this light, any struggle for freedom is a struggle for freedom of action.

my definition of free will means that given a situation A, an entity knowingly has the choice between doing B, C, or D (or any other number of options), and can choose any one. Presented with the exact same situation, the entity will again have these options, and can easily choose to act differently.

Exactly what I mean by freedom of action.

If you are asked if you want either lemonade or tea to drink, then yes, you have freedom of action to either chose one of them. But given a certain situation at a certain time, you always will come to the same conclusion as your brain works itself to its decision-making process.

Bear in mind that if someone asks you the same question the next day, it is not the same situation anymore. It's merely a situation like A, namely A'.

The one who makes the decision at situation A' is not the same person anymore as they were at situation A. You could think "I drank lemonade yesterday, so I won't today." Or "That tea yesterday was too bitter, I want something sweet."

Yet you can only realize and do what you want but you cannot freely decide what to want.

Of course you could have different desires competing, e.g. "I want to make a diet" and "I want something sweet", yet given which desire is stronger you will act on it accordingly.

given a situation A, a computer will respond with action B, every single time.

Only a primitive program that does not store states will do so. A computer will react differently in situation like A if other dynamic side-conditions are taken into accounts as well.

Yet given the same dynamic side-conditions, the same conclusion will be derived.

The brain is a complex self-programming machine that reprograms itself according to evaluations of past events, and hence will produce different output when presented with similar input. It's what we call learning by experience. (Those experiences could also just be mind-experiments. Just thinking what happens if you jump off a cliff is enough to make you realize that doing so would be unwise.)

If everything is cause and effect, does that mean that we effectively cannot impact what occurs around us and in our heads?

You impact the world around you. And you are impacted by the world. No free will needed.

And what happens in your head is not affected by 'you' but that very process is you. Your very identity.

That all our actions are the result of electromagnetic waves in our brains?

That is too simplistic. The brain gets input, analyses it, abstracts it, categorizes it, conceptionalizes it, puts it in relation with other concepts, and going from there derives or infers plausible causes of action.

It's not just the result of "electromagnetic waves", it's the result of a complex but deterministic (as in: "governed by the laws of physics") process.

It happens that the brain emits electromagnetic waves while doing it, yet I think it is possible though not feasible to build a brain using water pipes.