Does that mean that, for instance, G, in key G, will be in one place, but in key Eb, where G is M3, it'll be slightly different, and in Ab, where it's the leading note, it'll be different again? Does it mean that there is a possibility of seven different places where G lives?

No, it's worse than that. The location of any note can change in a single key, in a single piece, and in a single phrase. That is, it's not so much according to the key of a piece as it is according to the harmonic context of each note. Consider that G in the context of a piece in A minor. The G could be the fifth of a C-major chord. If you get to the C by way of an F chord, and you want the major third between the F and the A to be pure, the ratio between A and C will be 6/5:

A = 440 Hz

C = A * 6/5 = 528 Hz

G = C * 3/2 = 792 Hz

The ratio of G to A is therefore 9/5, which is about 17.6 cents higher than an equal-tempered G at 784.0 Hz.

Now G could also be a fourth above D or, equivalently, a fifth below it. Going from A to G on the circle of fifths, you get a ratio of 16/9:

A = 440.0 Hz

D = A * 4/3 = 586.7 Hz

G = D * 4/3 = 782.2 Hz

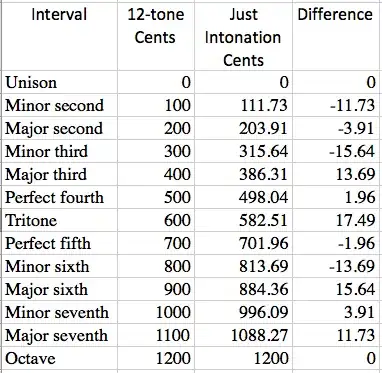

That is pretty close to an equal-tempered G, being about 3.9 cents lower. The ratio of the two Gs, 81/80, or about 21.5 cents, is known as the syntonic comma.

So, when you're playing in A minor, and there's a section of the piece where the harmony is focused on D, you might use a different G from the one in another section of the same piece where the harmony is focused on F and C.

You can even find situations where it makes sense to change the pitch of a repeated note because of the harmonic context. This happens, for example, in the final chorale of Cantata 78, Jesu, der du meine Seele. The piece is in G minor, so we'll try to keep G constant. The first pitch where we'll notice trouble is A.

The first four measures are fairly stable and end on the dominant, D major. The next four measures essentialy repeat this, and measure 10 also starts on D major:

X:1

L:1/8

M:4/4

K:Gm

%%score S A T B

V:S clef=treble name="S"

V:A clef=treble name="A"

V:T clef=treble name="T"

V:B clef=bass name="B"

% 1

[V:S] A2 B2 c2 A2 | B2 AG G2 F2 |

[V:A] ^F2 G2 G2 F2 | F2 F2 =E2 C2 |

[V:T] d2 d2 c2 c2 | Bc d2 cB A2 |

[V:B] D,2 G,F, =E,2 F,2 | D,2 B,,2 C,2 F,2 |

In analyzing the frequencies, we'll give everything as the ratio with the frequency of G, keeping all the ratios between 1 and 2 by multiplying by a power of 2 where necessary (for example, if we calculate a frequency of 40/9, we'll divide by 4 to get 10/9).

Calculating the frequencies for F# and A from D=3/2, we get F#=15/8 and A=9/8. The tenor carries the D from the first beat to the second, giving us a standard G minor chord of G=1/1, Bb=6/5, and D=3/2. The alto carries the G into the third beat, giving us C=4/3 and E=5/3. The tenor carries the C into the fourth beat, giving F=16/9 and A=10/9.

Here we have our first problem. The soprano just started the phrase singing A=9/8, and now they're singing A=10/9. The ratio of those frequencies is 81/80, the syntonic comma. In fact, if we keep all of the fifths and unisons perfectly in tune, the pitch of the final chord will be lower than that of the starting chord by this ratio. A progression like this is called a comma pump.

How can we fix that? Since the soprano melody is the starting point of the composition, what happens if we tune that chord to the sopranos singing A=9/8 to match their first note, instead of tuning it to the tenors? The bass and alto F becomes F=9/5 instead of F=16/9. Perhaps most oddly, the tenors would have to raise the pitch of the repeated C from C=4/3 to C=27/20. The basses would have to sing a very large half step of 27/25 (33 cents larger than an equal-tempered half step, and 21 cents larger than the usual just half step of 16/15, which is already somewhat large at 112 cents). But when we get to the end of the piece, we'll be back where we started.

But there's still a problem. We're giving priority to the sopranos, and they have an odd interval between their A=9/8 and their C=4/3. That's a minor third of 32/27 instead of 6/5. But hey! If we put the C in beat 3 at C=27/20, the tenors don't have to change the pitch of the repeated C between beats 3 and 4. This could be good. What implications does it have?

If the C of beat 3 is C=27/20, then the G must be G=81/80. Perhaps we can forgive an unstable G in this part of the piece, since we're moving to the relative major. But if we use that G in the previous beat, the D would also have to be raised by a syntonic comma, so either the tenors would have to alter the pitch of their repeated D between beats 1 and 2 or the altos would have to raise the pitch of their repeated D between beats 2 and 3. There's no way to keep all the harmonic and melodic intervals pure while also ending the piece where we started.