For CriglCragl and the common view expressed, I think CC is actually demonstrating that AI is indeed in a crisis of science. CC says the idea that AI is in a crisis of science is:

both wrong, and misguided, in a way that people familiar with the

subject will have very little patience for.

(I presume CC's original opening line “"You question appears to be comically ill informed" indicates that they fully believe they are indeed among those familiar with the subject.)

But as everyone knows, a crisis of science comes about precisely because a research programme has failed to make fundamental progress, and a thought experiment exposes that failure in ways that isolate the root of crisis with a clarity unobtainable in the laboratory.

CC agrees there is a fundamental failure:

Artificial General Intelligence [-] we just don't know when [it] will

be possible

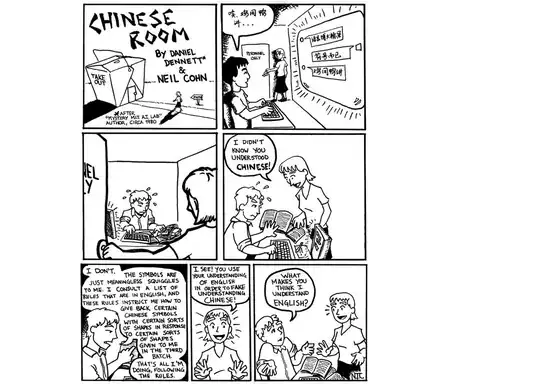

If CC understands the CRA then they know it exposes this failure by appeal to the fundamental nature of computation. (No one seems to be denying computation is the purely syntactic manipulation of symbols without accessing their meanings.)

And the third ingredient of any crisis of science is that the Illuminati can't conceive of themselves as being wrong; and because of their psychological dependence on unbridled falsehood react emotionally to any suggestion of error.

So I think CC's comment which expresses a common view within AI is quite a clear answer to my question: YES, AI is in a crisis of science.

About the CRA, this is the key thing to me, and it addresses some other of the comments above. The CRA can be boiled down to just one issue: the intrinsic meaninglessness of the symbol. If you say computers manipulate symbols and do nothing else (as Searle does) and given that symbols in themselves say nothing about what they mean, then the computer is forever a prisoner in a universe of meaningless syntax and formality. The system reply, the many mansions reply, the robot reply, all the replies are beside the point. Unless the inherent meaningless of the symbol can be overcome, computers will never be intelligent. This is Searle's core position and I think is clearly a crisis.

Just for the sake of completeness, I've been given a -1 score. Because of this sort of unhelpful and I have to say in a sense arrogant thing I gave up on PSE a while ago and switched to academia.edu. A few days ago I posted exactly the same question there in the form of a short paper. The second respondent was Pat Hayes, AI royalty, who answered with well-thought-out and constructive arguments, as of course one would expect. In all the comments there was no beating of the hairless chest. I'm sure PSE gives good guidance to novices, but I think it's simply wrong to expect balanced debate (Crigl please take note).

According to the voting balloon, a negative vote means "The question does not show any research effort". So (to cut and paste some recent relevant research effort):

...despite seven decades of prodigious funding and effort, nothing

approaching AGI has been demonstrated. Instead, serious practical and

theoretical difficulties have arisen including those known as the

problem of design (1), the problem of machine translation (2), the

frame problem (3), the problem of common-sense knowledge (4), the

problem of combinatorial explosion (5), the Chinese room argument (6),

the infinity of facts (7), the symbol grounding problem (8), and the

problem of encodingism (9). And for "deep learning": edge cases (10),

noisy data-sets (11) adversarial attack (12) and catastrophic

forgetting (13).

- Ada Lovelace, 1843, "Note G", quoted in "The Turing Test," Stanford

Encyclopedia of Philosophy, section 2.6,

https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/turing-test. Also see John von

Neumann, "First Draft of a Report on the EDVAC," (Moore School of

Electrical Engineering, University of Pennsylvania, 30 June 1945), 1

- Yehoshua Bar-Hillel, "The Present Status of Automatic Translation of

Languages," in Advances in Computers, ed. Franz L. Alt (Academic

Press, 1960), 1: 91-163.

- J. McCarthy and P. J. Hayes, "Some Philosophical Problems from the

Standpoint to Artificial Intelligence," in Bernard Meltzer and

Donald Michie (eds.) Machine Intelligence 4 (American Elsevier,

1969), 463-502. Also see Dreyfus, "Alchemy and Artificial

Intelligence," 29, 39, 68.

- Hubert L. Dreyfus, "Alchemy and Artificial Intelligence," (The RAND

Corporation, P-3244, December 1965), 39.

- James Lighthill, "Artificial Intelligence: A General Survey,"

section 3 Conclusion, in Artificial Intelligence: A Paper Symposium

(Science Research Council of Great Britain, July 1972). Also

Dreyfus, "Alchemy and Artificial Intelligence," 39.

- John R. Searle, "Minds, Brains, and Programs," Behavioral and Brain

Sciences 3, no. 3 (1980): 417-457.

- Dreyfus, "Alchemy and Artificial Intelligence," 39. Also Daniel C.

Dennett, "Cognitive Wheels: The Frame Problem of AI," in The Robot's

Dilemma: The Frame Problem in Artificial Intelligence, ed. Zenon W.

Pylyshyn (1984; Ablex, 1987), 49.

- Stevan Harnad, “The Symbol Grounding Problem,” Physica D 42 (June

1990): 335-346.

- Mark Bickhard and Lauren Terveen, Foundational Issues in Artificial

Intelligence: Impasse and Solution (Elsevier, 1995).

- Overview of issues: Philip Koopman, "Edge Cases and Autonomous

Vehicle Safety," (paper presented at the Safety-Critical Systems

Symposium, Bristol UK, 7 February 2019).

- Overview of literature: Gupta, Shivani and Gupta, Atul, "Dealing

with Noise Problem in Machine Learning Data-sets: A Systematic

Review," Procedia Computer Science 161 (Elsevier, 2019): 466-474.

- Survey: Anirban Chakraborty et al., "Adversarial Attacks and

Defences: A Survey," (arXiv:1810.00069v1, 28 September 2018).

- James Kirkpatrick et al., "Overcoming Catastrophic Forgetting in

Neural Networks," Proceedings of the National Academy of sciences

114, no. 13, (2017): 3521-3526.