Francisco Suárez

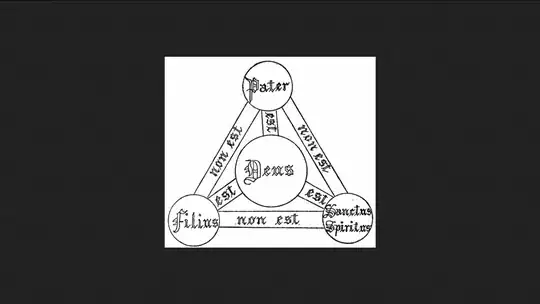

Suárez discusses the applicability to the Persons of the Trinity of this form of the principle of non-contradiction,

in On the Various Kinds of Distinctions p. 59 (Disputationes Metaphysicæ, Disputatio VII, De Variis Distinctionum Generibus),

- §2 The Signs or Norms for Discerning Various Grades of Distinction in Things

Quibus signis seu modis discerni possint varii gradus distinctionis rerum

- A Doubt Concerning the Separability of Distinct Things

Dubium occurrens de separabilitate rerum distinctarum

- Third exception: the divine Persons

Tertia de personis divinis ad invicem

The objection might be made that this argument is based on the principle gathered from Aristotle, Metaphysics, Bk. IV, text. 3,56 that things which are the same as a third thing are the same as each other — a principle which has no place in the Trinity; otherwise we should infer not only that one relation cannot exist without another, but that it is this other.

Dices, hoc argumentum fundari in illo principio Aristotelis, IV Metaph., text. 3: Quæ sunt eadem uni tertio, sunt eadem inter se, quod in Trinitate locum non habet; alioqui non solum inferretur unam relationem non posse esse sine alia, sed etiam esse aliam

56. The axiom is nowhere explicitly formulated in Metaphysica, IV, text 3. Junta VII fol. 31 vb. 32–58. Cf. Metaphysica, IV, 2, 1003b 22–34. But it is an obvious application of the principle of contradiction, which Aristotle discusses throughout this book.

(courtesy: Quaestiones Disp.)

and in the last section of this disputatio:

- §3 Comparison of “The Same” and “Other” Both with Each Other and with Being

Quomodo idem et diversum tum inter se, tum ad ens comparentur

- Explanation of an Aristotelian dictum (p. 67)

Expositio pronuntiati aristotelici

Finally, we can gather from the foregoing doctrine the meaning of an axiom enunciated by Aristotle in the fourth book of the Metaphysics:72 Things which are the same as a third thing, are the same as each other. Due proportion must be observed in applying this principle. If two things are in reality identical with a third thing, they will also be identical with each other in reality, although they may be diverse in concept. And if they are identical with a third thing both in reality and in concept, they will be identical with each other in the same way. In creatures and in finite things this principle avails absolutely. But in an infinite thing, such as is the divine essence, the maxim is not verified, absolutely speaking, since on account of its infinity the divine essence can be identical with opposite relations which, because of this opposition, cannot be identical with one another, except in the essence alone. But we have dealt with this problem on another occasion.73

Ultimo potest ex dictis colligi, quomodo sit intelligendum illud axioma quod Aristoteles posuit IV Metaph.: Quæcumque sunt eadem uni tertio, sunt eadem inter se; intelligendum est enim cum proportione, nam si sunt eadem re uni tertio, simili modo erunt eadem re inter se, poterunt autem esse ratione diversa; si autem re et ratione sint uni tertio eadem, erunt eodem modo eadem inter se. Sed hoc principium in creaturis, et in rebus finitis simpliciter tenet; in re autem infinita, qualis est divina essentia, non verificatur illa maxima absolute loquendo, quia propter suam infinitatem potest esse idem relationibus oppositis quæ propter oppositionem inter se idem esse non possunt nisi tantum in essentia; de quo alias.

72. See note 56.

73. De Sanctissimo Trinitatis mysterio, Lib. IV, cap. 3; in Vol. I of the Vivès edition.

St. Thomas Aquinas

In De Sanctissimo Trinitatis mysterio, Lib. IV, cap. 3, Suárez discusses St. Thomas's solution in Summa Theologica I q. 28 a. 3 "Whether the relations in God are really distinguished from each other?" arg./ad 1. St. Thomas writes:

Objection 1: It would seem that the divine relations are not really distinguished from each other. For things which are identified with the same, are identified with each other. But every relation in God is really the same as the divine essence. Therefore the relations are not really distinguished from each other.

Videtur quod relationes quæ sunt in Deo, realiter ab invicem non distinguantur. Quæcumque enim uni et eidem sunt eadem, sibi invicem sunt eadem. Sed omnis relatio in Deo existens est idem secundum rem cum divina essentia. Ergo relationes secundum rem ab invicem non distinguuntur.

Reply to Objection 1: According to the Philosopher (Phys. iii), this argument holds, that whatever things are identified with the same thing are identified with each other, if the identity be real and logical; as, for instance, a tunic and a garment; but not if they differ logically. Hence in the same place he says that although action is the same as motion, and likewise passion; still it does not follow that action and passion are the same; because action implies reference as of something "from which" there is motion in the thing moved; whereas passion implies reference as of something "which is from" another. Likewise, although paternity, just as filiation, is really the same as the divine essence; nevertheless these two in their own proper idea and definitions import opposite respects. Hence they are distinguished from each other.

Ad primum ergo dicendum quod, secundum philosophum in III Physic., argumentum illud tenet, quod quæcumque uni et eidem sunt eadem, sibi invicem sunt eadem, in his quæ sunt idem re et ratione, sicut tunica et indumentum, non autem in his quæ differunt ratione. Unde ibidem dicit quod, licet actio sit idem motui, similiter et passio, non tamen sequitur quod actio et passio sint idem, quia in actione importatur respectus ut a quo est motus in mobili, in passione vero ut qui est ab alio. Et similiter, licet paternitas sit idem secundum rem cum essentia divina, et similiter filiatio, tamen hæc duo in suis propriis rationibus important oppositos respectus. Unde distinguuntur ab invicem.

John of St. Thomas

John of St. Thomas (João Poinsot), O.P., 1589-1644, compares Suárez's and St. Thomas's solutions in Cursus theologicus d. 12 a. 3 n. 31 arg./ad 2, noting their differences in defining the aforementioned logical principle:

This Mystery is not Contrary to the Principles of the Natural Light of Reason.

Non Contrariatur Principiis Luminis Naturalis Hoc Mysterium.

[Objection:] 28. […] The second principle known by the natural light [of reason], which destroys this mystery, is that: Whatever are similarly one in a third, are similarly between themselves, upon which the entire rationale of the syllogistic art and deduction is based. But this principle is denied in this mystery because three Persons are one and the same in the divine essence, but between themselves they differ and are not one.

Secundum principium naturali lumine notum, quod destruit hoc mysterium, est illud: Quæcumque sunt eadem uni tertio, sunt eadem inter se, super quod tota ratio syllogisticæ artis fundatur, et omnis firmitas illationis, et consequentiæ. Hoc autem principium negatur in hoc mysterio, quia tres Personæ sunt unum et idem in essentia divina: inter se autem differunt, et unum non sunt.

[…]

31. St. Thomas replies to the second [objection] in [Summa Theologica I] q. 28 a. 3 ad 1, that the principle: Whatever are similarly one in a third, etc. is understood by the philosopher in III Physics text 21 to apply to things that are similarly one in a third, in the thing and in reason, but not of things that differ in reason. The holy doctor explains the same principle in another way [Super Sent.] I d. 33 q. 1 a. 1 ad 2, which is understood: Those which are similarly one in a third, are the same between themselves in the same way by which they are the same to the third, and not otherwise nor in another manner. And so three Persons are the same one by the third, i.e., in the divine substance, in the absolute rationale, and between themselves they are also one in the same absolute and substantial rationale; however, they are not one between themselves relatively, because in that third they are not one relatively, but only absolutely. Therefore, that natural principle—that whatever are similarly one in a third are similarly between themselves, i.e., in the same way by which they are similarly one in the third—saves this mystery; but, in another way it is not necessary that they be similarly between themselves, but by one only, by which in that third they are one.

Ad secundum respondetur ex D. Thoma infra q. 28 art. 3 ad 1, quod illud principium: Quæcumque sunt eadem uni tertio, etc. intelligitur a philosopho III physic. textu 21 de his, quæ sunt eadem uni tertio, re, et ratione, non autem de his quæ differunt ratione. Idem principius explicat aliter s. doctor in I, distinct. 33, q. 1, art. 1 ad 2, quod intelligitur: Ea quæ sunt eadem uni tertio, sunt idem inter se, eo modo, quo sunt eadem illi tertio, et non aliter, nec alio modo. Et sic tres Personæ sunt idem uni tertio, scilicet substantiæ divinæ, in ratione absoluti, et inter se etiam sunt unum in eadem ratione absoluta et substantiali, non tamen sunt inter se unum relative, qua nec in illo tertio sunt unum relative, sed solum absolute. Salvat ergo mysterium hoc illud principium naturale quod: Quæ sunt eadem uni tertio, sunt eadem inter se, videlicet eo modo, quo sunt eadem uni tertio; alio autem modo non est necesse quod sint eadem inter se, sed eo solum, quo in illo tertia unum sunt.

Others explain that principle thus: Whatever are similarly one in a third, are similarly between themselves, if they be similarly one in the third equally and simply, but not if they be similarly one in the third unequally. But the divine relations are unequally related with respect to the essence, because whichever of them so affects the essence leaves place for the other; and so all the three Persons equal it, not one only. This explanation coincides entirely with the first explanation of St. Thomas.

Alii explicant illud principium sic: Quæ sunt eadem uni tertio, sunt eadem inter se, si sint eadem uni tertio adæquate, et simpliciter, non vero si sint eadem uni tertio inadæquate. Relationes autem divinæ inadæquate se habent respectu essentiæ, quia quælibet illarum ita afficit essentiam, quod alteri locum relinquit; et sic omnes tres Personæ adæquant illam, non una tantum. Quæ explicatio fere coincidit cum priori explicatione D. Thomæ.

Others say that principle is to be understood thus, that: Whatever are similarly one in a third, are similarly between themselves, without any opposition intervening between those extremes, that they be one between themselves more than that unity by which are the same in one by a third. In fine, Fr. Suárez lib. IV de Trinitate, cap. 3 denies that principle to be true, except in created things according to their limitation, even false if it be extended to divine things, according to their infinitude, in which place it also has absolute perfection, in which all are one, and relative [perfection] between what is opposed. Fr. Vasquez also teaches this in tome II, in the first part, disp. 123, c. 2, and others who teach that principle only holds where there is limited power, not where there is infinite eminence embracing the absolute genus with supreme unity, and relative [eminence] with correlative opposition. From which all agree how that natural principle is not destroyed in this mystery, but remains unharmed, understanding it in its truth and legitimate sense.

Alii dicunt illud principium sic esse intelligendum, quod: Quæ sunt eadem uni tertio, sunt eadem inter se, nisi obstet aliqua oppositio inter illi extrema, ut sint unum inter se magis, quam illa unitas, qua sunt idem in uno tertio. Denique p. Suarez lib. IV de Trinitate, cap. 3 negat illud principium esse verum, nisi in rebus creatus propter suam limitationem, falsum tamen si extendatur ad divina, propter suam infinitatem, in qua locum habet et perfectio absoluta, in qua omnia sunt unum, et relativa inter quæ est oppositio. Quod etiam docet p. Vasquez II tomo, in prima parte, disp. 123, c. 2, et alii, qui docet illud principium tenere solum, ubi est limitata virtus, non ubi est eminentia infinita complectens genus absolutum cum summa unitate, et relativum cum oppositione correlativa. Ex quibus omnibus constat quomodo illud naturale principium in hoc mysterio non destruatur, sed maneat illæsum, intelligendo illud in sua veritate, et legitimo sensu.

cf.: