Well, it's late at night so I'm sure I'm going to repeat past mistakes and screw something up here. But let's give it a try.

You start with the original sentence:

∀w(∀v((v=w∧φ(v))⇔φ(w)))

From there we just need to discharge the outermost quantifier, instantiating to the term "t" (assuming we have such a term laying around):

∀v((v=t∧φ(v))⇔φ(t)))

Then we instantiate once more:

(r=t∧φ(r))⇔φ(t)

Finally, we existentially generalize:

∃v(v=t∧φ(v))⇔φ(t)

To a sleep-deprived version of me, that seems like what you're after. If I messed something up, lemme know and I'll revisit the question with a clearer head.

Update

Ok, so I've typeset proofs of each of the principles (the conditional and the biconditional versions) as tree proofs in the style of Graham Priest's Introduction to Non-Classical Logic. Let me know if you have problems understanding them.

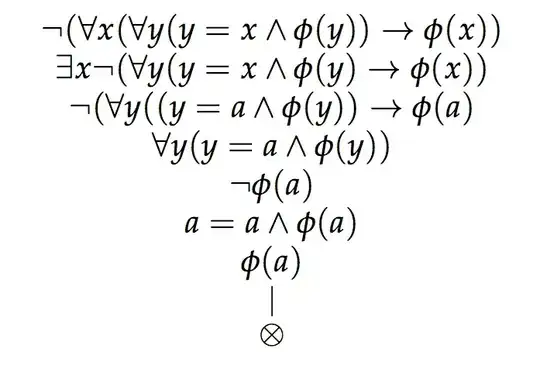

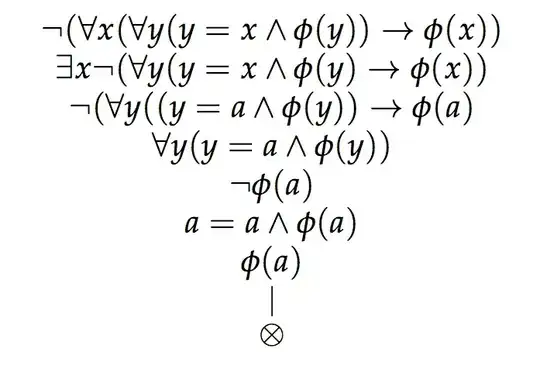

First the conditional, which I prove via reductio ad absurdum by assuming its negation:

Since the proof terminates in a contradiction (a is both φ and not-φ), the negated conditional leads to contradiction and so our original conditional is valid.

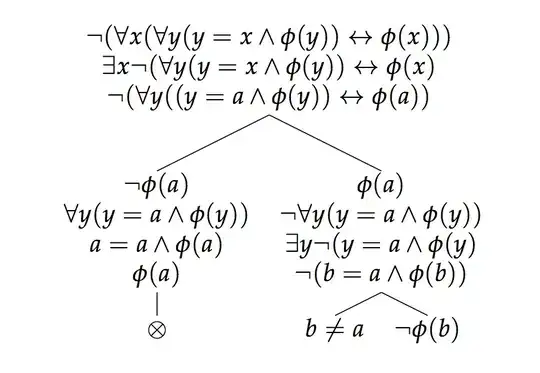

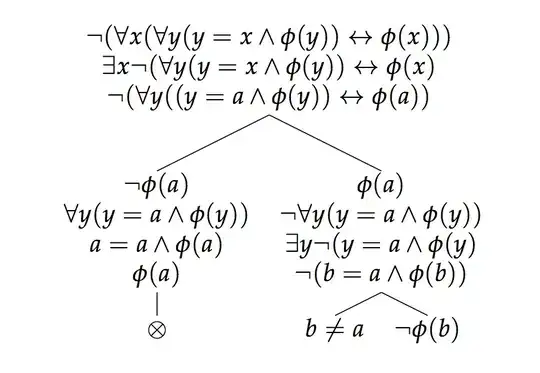

Ok, so the conditional is valid, what about the bicondtional? Again, I don't think it is valid. Consider the following attempted proof:

Now, the left hand branch leads to contradiction and so closes. The right hand branch, on the other hand, involves no contradictions and so the negation of the biconditional isn't invalid. But if the negation of the biconditional isn't invalid then the biconditional isn't valid.

The problem is the right-to-left side of the biconditional, since if we start off assuming that b is φ that doesn't guarantee that b is the only object in the domain. If there's another object a that is not identical to be, then though b is φ, the consequent of the right-to-left side comes out false since a is not identical to b.