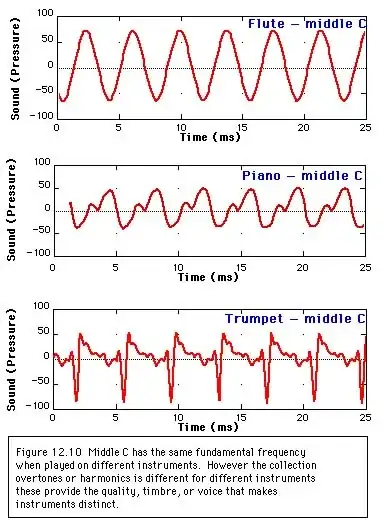

Essentially all instruments produce overtones, which are frequencies other than the dominant frequency of the note.

The use of "essentially" there got me thinking. Are there any instruments which do not produce overtones?

Essentially all instruments produce overtones, which are frequencies other than the dominant frequency of the note.

The use of "essentially" there got me thinking. Are there any instruments which do not produce overtones?

A tuning fork comes close, though amplifying it by placing it on some resonating object - a wooden table, piano case, or try your head :-) - will add some harmonics.

The tone of a flute, especially in the higher register, is close to a sine wave.

Note that we're talking about the sustain portion of a note. Both tuning fork and flute produce much more complex sounds as a note is attacked. You could mistake a tuning fork for a flute if the attack portion of a note was chopped off. I don't think you'd confuse the two if the attack was also heard though!

This principle was put to good use in 'Hybrid Synthesisers' like the Roland D50 or Yamaha SY range. A short sampled attack was followed by a synthesised sustain and release. It combined a remarkable degree of realism and controllability with economical use of sample memory.

So your answer is: although some instruments have a sustain close to a sine wave, I can't think of one outside the test bench that lacks a more complex attack.

– user45266

Jun 03 '19 at 17:13

– user45266

Jun 03 '19 at 17:13

I've heard it claimed that human whistling comes very close to being a perfect sine wave:

The video here seems to show only one peak on the spectrograph, supporting a nearly perfectly sinusoidal waveform.

As far as I know every instrument produces overtones. Some might think that unpitched percussion don't have overtone, but they produce them as well.

However, there are some electronic instruments, such as synthesizers (sine waves) which can be played without producing any overtones, but every acoustic instrument does.

If I'm correct the ocarina might be the instrument which come as close as possible to creating 'no overtones'. In fact, they do create overtones as well, but because of their shape, the overtones are actually many octaves above the keynote scale.

It is worth looking at the reason WHY there are so few instruments that produce sine waves. It is clearly fairly difficult, from the point of view of physics, to make a sine wave without electronics, but people could have tried to get close if they wanted to.

The psycho-acoustic answer is that few attempted this because it does not sound interesting. It is notable that, of the examples suggested, most are:

Not designed for human entertainment (e.g. tuning fork)

Designed as part of something (e.g. one stop on a synthesizer, to be played with others)

Designed with other features to make the sound more interesting (e.g. theramin)

One instrument that gets fairly close is the Stylophone. This produces a sine wave - in theory - simply because this was the cheapest sound to aim for in an electronic instrument. Any deviation from the sine wave is not caused by aesthetic considerations, but by an over-riding desire for cheapness in the design brief. That is to say, the overtones are caused entirely by the cheap amplifier, cheap speaker and cheap plastic case.

frequencies other than the dominant frequency of the note

Any finite wave has frequencies other than the dominant frequency. Single frequency is only possible for a sinusoid that has lasted since forever with constant amplitude and will continue to do so.

For any finite wave you will be able to perceive (with your ear or any physical measuring device) a bundle of neighbouring frequencies like seen in the image included in another answer. The width of the bundle is limited by duration of the signal.

NOTE: This answer does not discuss overtones in the common meaning of the term (multiples of fundamental frequency) but the definition from the question (quoted above).

You can create pure a sine wave with some electronic generators. Another way is to use software. I created a series of pure sine waves in wav files at various frequencies for a hearing test. They don't sound like any real instrument that I have ever heard. So, that says that no instrument that I have heard produces a pure sine wave. Of course, I have not heard all instruments but I have heard many. The closest might be a flute but it still was recognisably different. I do not find a pure sine wave appealing.

Note that there is more to the difference between the sounds of various instruments than the harmonics: e.g. attack, decay, stability of pitch, etc. Back in the days of cassette tapes I had a tape of piano music stretch badly. It no longer sounded at all like a piano, it sounded like a musical saw. The harmonics would not have been changed (much) by the stretching. It indicated that an essential part of the piano sound is the stability of the pitch. For that reason, since then, I always used solo piano music to assess turntables. It is a long time since I did that though as I was an immediate convert to CDs. Partly due to this experience.

There are already quite a number of "instruments" listed in other answers but I think a subset of organs may reproduce an sinusoid approximate.

On the electrical side of things the Hammond organ used a spinning tonewheel and electrical pickup to generate near sines. Each key had several wheels spinning at multiples of the fundamental frequency. You could adjust valves controlling the strength (amplitude) of each harmonics -- an early prototype of additive synthesizers. Hence I will argue that the Hammond organ, unlike other instruments, was designed with sinusoidal production in mind. You could also argue that the Hammond was simply an attempt to replicate the fuller feel of true pipe organ.1 A live demonstration of can be found on youtube (with accompanying spectrogram).

There's also the original Telharmonium, a gargantuan factory-sized machine that produced near sines in a similar way.

On the Aerophone side of the things, there are certain pipes which are highly sinusoidal including the Tibia pipes of which you can hear a bit in the first 30 seconds of this video.

1You could also argue that the Hammond was simply an attempt to replicate the fuller feel of true pipe organ.

See also the lasso d'amore at which reference is stated "the timbre of the notes [...] are 'almost all fundamental,' according to Fourier analysis (similar to sine waves)." It is possible to play the instrument at a speed so near the transition from one resonance to another that two simultaneous pitches are produced. (This tends to be possible at higher speeds, at which it is difficult to prevent having different speeds in different arcs of the arm movement producing different tones from each arc.)

A pure sine wave is the only instrument that plays a tone without any overtones. This isn't a strange coincidence. An instrument's timbre is the consequence of its unique overtones - which ones it has, which ones are loudest, whether some overtones are slightly flat or sharp, and how the overtones mutate over time. Since there's only one timbre profile that can come from having no overtones, it shouldn't come as a surprise that there's only one sound that fits the bill. And when you strip all overtones from a sound wave, a sine wave is exactly what you get.

By far, I'm no expert in this, but here's my best shot.

Timbre is the result of a specific series of overtones sounding off louder than others. We are looking for a timbre that only has the fundamental sounding off and nothing sounding above it. I suppose anything that could produce a single sine wave would be your answer. Perhaps an organ with only one tone sounding?