Okay I'll admit, I don't know everything about music theory but I was pretty sure that any given diatonic (7 note) scale contained particular notes that defined the scale and were unique to the scale and that those notes would be the same regardless of which direction you were moving in said scale (ascending or descending).

Then I came across This Question which is specifically about the A-Minor scale and more particularly apparently about the A-Melodic-Minor Scale.

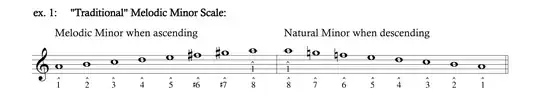

The accepted answer claimed

You play G-natural and F-natural when descending in a Melodic-Minor Scale

and a different user posted in a comment

A melodic minor has two extra sharps on the way up and none on the way down.

I had a hard time believing that the A Melodic-Minor scale (or any other Melodic Minor Scale) would have different notes depending on if it was played in ascending or descending order so I turned to my favorite search engine and found this on basicmusictheory.com about the A Melodic-Minor Scale:

Be aware that when descending this scale, sometimes the notes of the A natural minor scale are played instead.

So basically I learn that when you play the A Melodic-Minor scale on piano you play these notes when ascending:

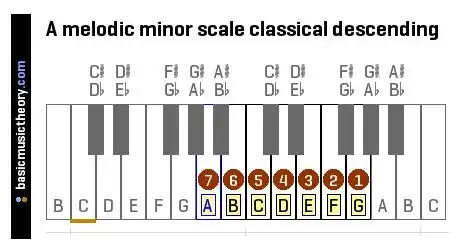

But when descending it is often played with the notes pictured below:

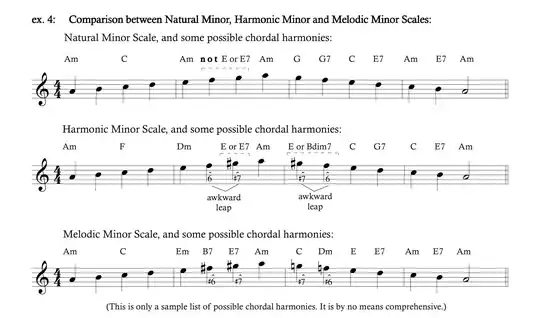

This apparent aberration in logic is not specific to the A Melodic Minor scale but rather applies to any and all Melodic Minor Scales. So this question is not about just the A Melodic Minor Scale but rather ALL Melodic Minor Scales.

I am sure there actually is some logic to this unexpected revelation - but I would like for someone to explain why in a melodic minor scale the notes can vary depending on which direction you are moving in the scale.

Also - is the melodic minor scale the only type of scale where this commonly occurs?