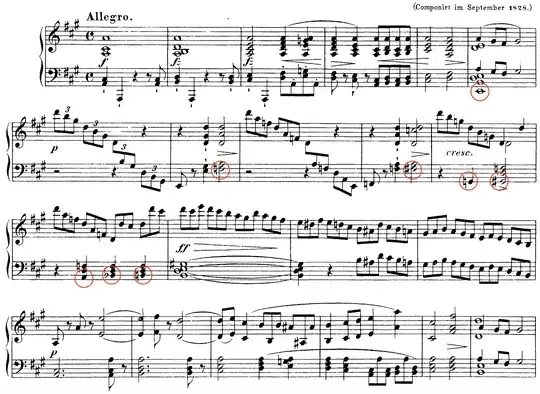

Being confused about Schubert’s harmonic progression seems to be a common thing. This sonata starts on a big cadenza on A major. But instead of resolving the dominant in measure 6 he delays resolution to then resolve to the IV in minor (d minor) with the third in the bass. This has a bit of a similar character to a deceptive cadence. Then comes the part you are confused about. The IV in minor gets sharpened to a dominant 7 on the IV. This then resolves to the VII (G major). We then get a chromatically rising bass which gives us G# diminished 7, D minor, Bb major, B diminished (II) upon which we get a dominant which finally resolves to to the tonic in measure 16.

So the whole thing can be seen as delaying the resolution of this beginning cadence. Now as the chord change you have given us is simply a change of mode it is by itself a bit quirky, but what makes this particularly unround is the way the alto rises in the same direction as the bass with the other voices remaining, especially since bass and alto move into a dissonance. If one were to voice this as f-a-d-a-d → f#-a-c-a-d it would sound much more rounded.

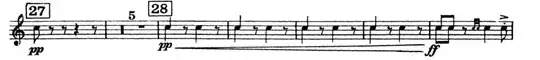

But if you take a look at the accent marks here (which Brendel absolutely fails to deliver) it should be clear that Schubert is not going for roundedness here, but for bite and harmonic instability.