I am not a skilled cellist, but I just grabbed my daughter's cello and played it successfully. Mind you, my tone was such that my wife looked up and said "What are you doing? and why are you doing that to me?"

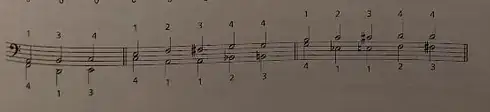

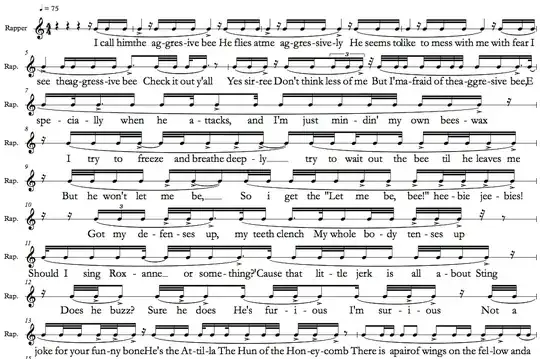

This range is, as John says, only about an inch from the end of the fingerboard. The C and the B "overlap" each other's space so that, as I played the C with 4th finger, I had to push the 4th out of the way as I placed the 3rd finger. Playing in this range is definitely for accomplished players. For a professional the range itself wouldn't raise eyebrows, but it might indeed scare away intermediate players.

Then, there's an added challenge to playing double stops in this range. Playing double stops in tune in any range adds an extra thing to worry about, and intonation is trickier in high registers.

But the big issue is bow control. The fairly slow tempo of 72 actually makes this much more challenging, especially if this is loud. I apologize for a lengthy digression, but to explain this, I'll have to explain a bit about how we control tone with the bow:

There are three variables: bow speed, the weight of the bow on the string, and the "contact point," i.e. how close the bow is to the bridge or fingerboard. You can manipulate all three in various combinations, up to a point. If you have a very heavy, very slow bow, you get a "crunch" sound. But then if you move closer to the bridge you can get away with that same combination; you can move slower for a given weight, or press harder for a given speed. And the opposites are true; a very fast, light bow at a medium contact point gives a breathy whistling tone. And as you move away from the bridge, the "crunch" sound happens at an even lower ratio of weight to speed (in other words, what would be a "normal" weight for a "normal" speed is either too heavy or too slow as you move toward the fingerboard).

Now, when you play high on the string, you have to move closer to the bridge anyway. When your vibrating string length is only 4 inches, then playing 1 inch from the bridge is a quarter of your total length; it would be like playing way over the fingerboard in first position. And that means the entire range of acceptable contact points is shrunk: straying a half-inch toward or away from the bridge might be like moving by 1.5 inches in lower positions. So to make a good, healthy tone in this range, you must keep an absolutely steady balance of weight, speed, and very exact contact point. And if you want it loud, that means even more weight, which means more speed to match, or moving closer to the bridge. And if these are long notes—like, say, whole notes at 72, then there's an absolute cap on speed; you can't move too fast or you'll run out of bow. So that means more weight and even closer to the bridge. If this is f or above, I'd probably ignore that slur, and would do a "reverse hairpin" or something of the sort during the double stops to save bow—drop in volume after articulating the note, then swell back again. And then double stops complicate the matter because it means you have to carefully balance the weight on two strings; it's not just a matter of the weight your arm exerts on the bow, but the exact angle, to make sure you don't "ease up" on either the D or A simply by rocking in their direction.

So, all that to say: This is absolutely the kind of feature you might find in a cello concerto, and would be welcomed by a professional as a chance to show off their chops, but is not something to be shrugged off as no big deal; it would take practice and confidence.