Let me try to address this exact question as closely to its intent as possible. I like Michael Curtis's simple answer—no, there is no "best key." And yet—we could choose any key, so which should we choose?

Let's assume that you aren't writing for specific individuals, so you don't know their vocal ranges or abilities ahead of time. Let's assume that you're just trying to write something that is comfortably singable by as many people as possible.

Also, you talk about "a melodic line sung by a man and a woman, either in tandem or in alternation." This sounds to me as if you're looking to let the entire melody suit all voice types, so it could be sung in unison, and you're not focusing on "part writing," letting one of the voices be the "main melody" and another be "the harmony," singing other notes that simply sound good along with the melody. So the question becomes "What key should I pick to let as many voices as possible, of any sex, sing this melody comfortably?"

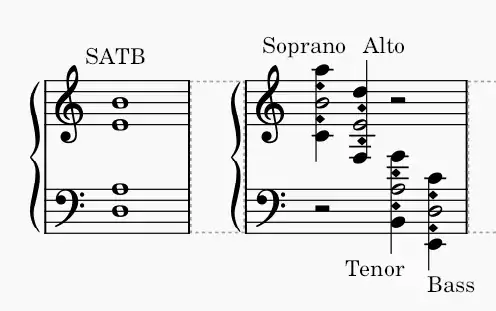

(Note: In unison singing, it's likely that women will be singing an octave higher than men. Look at Michael's image of the vocal ranges: there's only one note in common between soprano and bass, middle C, and that's at their extreme ends—not advisable for untrained voices, and not comfortable. But if you had Fs and Gs in your melody, then the soprano could sing them comfortably above middle C, and the bass could sing them below.)

As I mentioned in a comment, there could be one other thing to think of: convenience for instruments, or for reading the music. Keys with lots of sharps and flats could be hard for an instrumentalist to sight read, or could make the music a bit complicated (double sharps, etc.). It could be smart to consider only keys with up to 3 or 4 flats. This still leaves us with 7 to 9 keys.

Now, here's the unhelpful conclusion: It will depend on the song. First, if you want your song to be as singable as possible by as many people as possible, keep its range as narrow as possible. (Of course, then it's challenging to be expressive and memorable...) Even then, you have to ask yourself "what part of the key" your song's range sits in. For instance: "Mary had a little lamb" has a fairly narrow range; it spans a fifth. If you use solfege syllables, it uses Do, Re, Mi, Fa, and Sol—the "lower half" of the scale. But one could imagine a song that uses the notes Fa, Sol, La, Ti, and Do (the higher "Do"). (The "shave and a haircut" tune kind of works, except it lowers the "La".) It would have the same sized range, but you might have to choose a different key for the second song to "center" its notes in the ideal range. From Michael's image, we've already established that the ideal range would center around the notes F and G. So, for "Mary had a little lamb," the tune starts on the third-highest note of all the notes it uses. If we start on an F# (putting us in the key of D), we'll go down as far as D and up as far as an A. Starting on a G (key of E flat) could also be equally reasonable. In contrast, "Shave and a haircut" starts on its highest note, so an A or B flat might be a good starting note.