I would say there are two main reasons: one is acoustical and the second is the ranges of the SATB parts.

In Harmony, Walter Piston makes the point that close voicing with a large gap between bass and tenor mirrors the "chord of nature" and harmonic series.

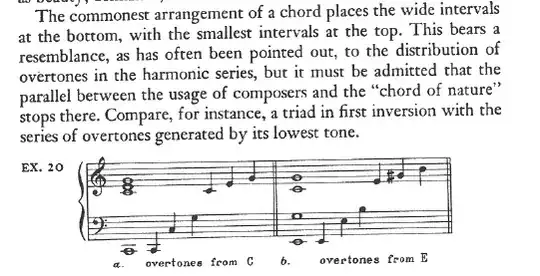

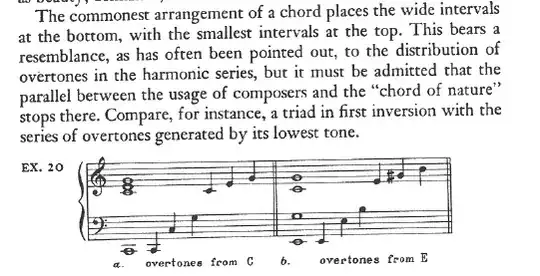

The commonest arrangement of a chord places the wide intervals at the

bottom, with the smallest intervals at the top. This bears a

resemblance, as has often been pointed out, to the distribution of

overtones in the harmonic series, but it must be admitted that the

parallel between the usage of composers and the "chord of nature"

stops there.

That isn't a direct explanation, and even Piston finds it dubious, but clearly spacing SAT with wider than an octave between adjacent parts is very unlike the chord of nature.

When you consider the comfortable ranges of the voices it's kind of hard to actually get the adjacent SAT voice spacing wider than an octave without the parts becoming awkward, moving into the extreme ends of the various ranges. In other words, if you write in a comfortable range for each part, you shouldn't have trouble with adjacent voice spacing exceeding one octave. The spacing "rule" can be viewed as a sort of backwards way to train one to write parts within comfortable ranges.

One way to break this rule is to push the alto down and the soprano up, the result being the three lower voices clustered together in a fairly low range, and if those voices are too low the sound may get "muddy." I think of that as another acoustical reason for the spacing rule.

There is a problem with questions that ask "why?"

I decided to add one more explanation.

I suspect the OP is expecting some kind of innate to sound or quasi-scientific answer to the question of "why" there are voice spacing guidelines. As Feynman points out in the linked video you can never answer persistent questions of "why?" The key question of voice spacing is "how?" And that leads to what I think is a third kind of explanation: procedural.

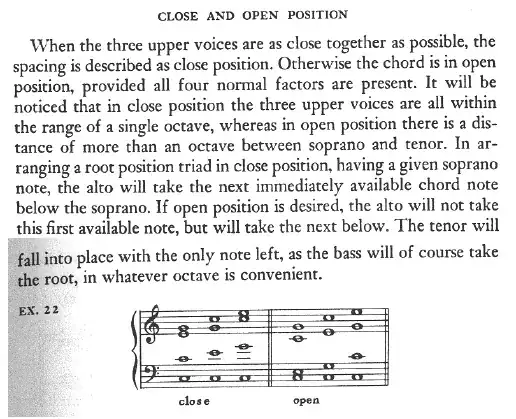

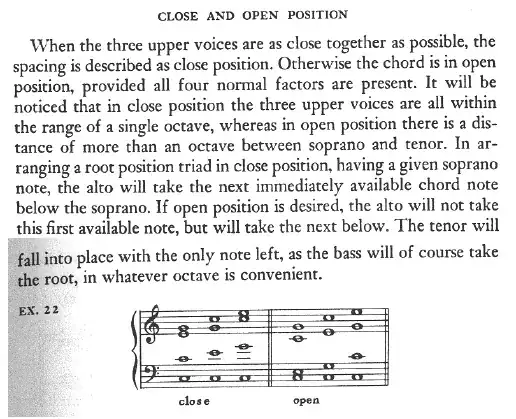

In Harmany, Piston explains close and open position simply by showing the inversion of the middle voice of the three close position triads to the lower octave generates the basic open spacings.

If open position is desired, the alto will not take the first

available note [below the soprano], but will take the next below. The

tenor will fall into place with the only note left, as the bass will

of course take the root, in whatever octave is convenient.

Procedurally inverting the alto will result in open position chords where the adjacent spacing of SAT will never exceed an octave. Piston's ex. 22 can be regarded as a chart of standard, desirable close and open chord spacing.

When writing an actual harmonization, both horizontal and vertical aspects are balanced. A harmonization is not only leading individual voices, it's also about a good vertical blend of voices. Swapping pitches between voices, inverting voices, are common approaches to getting a good balance. That means altering the linear direction of a part for the sake of a good vertical balance is normal when writing a harmonization. In Piston's text "good" vertical balance is exemplified in ex. 22.

There is yet another type of reason for this rule: pedagogical.

I've tried to get the OP to flesh out some detail from their text rather than focus on a single sentence, because I suspect they are misreading the intended meaning.

In Piston's Harmony (I focus on this text, because it is the one I have with the most elaborate discussion of voice spacing, my other texts cover it with only a sentence or single paragraph) he states:

Intervals wider than the octave are usually avoided between soprano

and alto, and alto and tenor...

Notice he includes the word "usually." Through out the text Piston makes clear there are no hard and fast rules. Artistic consideration can always override a rule of thumb or general procedure.

Bach's 371 Vierstimmige Choralgesänge is a good cure for harmony problems. It only took me scanning to the 5th or 371 to find an example of Bach "violating" two "rules" or part writing. He exceeded one octave between soprano and alto, and he crossed the alto and tenor!

BWV 267, An Wasserflussen Babylon

Why do harmony textbooks say the spacing between adjacent SAT voices shouldn't exceed one octave (and don't cross voices) even when Bach did it? Because it's rare when master composers do otherwise. From a pedagogical perspective if the teacher doesn't give students such guidelines, the student will write horribly spaced voicings.

So, if that is summarized, I would say the reasons are:

- acoustical clarity

- moderating the range of individual parts

- procedural, open spacing derived from inversion

- pedagogical, students follow the rule not actual composers