I've searched high and low for the meaning of the attached symbol but can't find the answer. Can you help me? The two horizontal Bars at the end of the line, some with a strike through.

-

1With a breve note, and others, one may wonder what the time signature of that piece could be. – Tim Sep 07 '22 at 07:12

-

My guess is that the breve is in one voice and the 16ths are in a different voice, in a common signature (4/2?). – Greg Martin Sep 07 '22 at 15:37

3 Answers

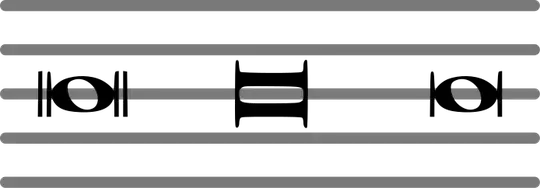

It is one of several forms of the breve, double note, or double whole note which, as its name suggests, has twice the duration of a semibreve or whole note. The three forms commonly used in modern engraving are shown below. The square form is more common before the middle of the 20th century.

The reason some are "struck through" is the same reason any other note is: the note's pitch is indicated by centering it vertically on either a line or a space on the staff (or, as in this case, on a ledger line above or below the staff).

Because this note is on the first ledger line below the staff, it could be any of the following, roughly in decreasing order of probability:

- C4, middle C, in treble clef

- E2 in bass clef

- D3 in alto clef

- B2 in tenor clef

- A3 in soprano clef

- G2 in baritone clef

- F3 in mezzo-soprano clef

- C2 in sub-bass clef

- E4 in French violin clef

Or, if you prefer, in decreasing order of pitch:

- E4 in French violin clef

- C4, middle C, in treble clef

- A3 in soprano clef

- F3 in mezzo-soprano clef

- D3 in alto clef

- B2 in tenor clef

- G2 in baritone clef

- E2 in bass clef

- C2 in sub-bass clef

It could also be any of those with a chromatic alteration because of an accidental or because of the key signature.

Another possibility is that it is a part for tenor voice written in octave-transposed treble clef, in which case it is C3 or some chromatic alteration thereof. Other octave transpositions are possible, for example if it comes from a piccolo part or a contrabass or contrabassoon part, but this is an increasingly distant digression from the actual question, so I'll stop with that.

- 16,807

- 2

- 33

- 61

That is a double whole-note on either middle C or bass E, depending on the clef. Double whole-notes last the length of two whole notes.

Wikipedia has an article with additional details: Double whole note

- 70,616

- 10

- 97

- 243

-

-

1@phoog The Wikipedia article isn't explicit, but is suggestive of "breve" and "double note". – Aaron Sep 07 '22 at 04:33

-

@phoog An article on symbols.com (https://www.symbols.com/symbol/double-whole-note-or-breve) indicates double whole note in the US and breve everywhere else. – Aaron Sep 07 '22 at 04:34

-

@phoog -since it's twice as long as a semibreve, it will be a breve in just about anywhere but USA, although not much music is written with bars long enough to support it. – Tim Sep 07 '22 at 07:10

-

4@Tim I believe the US terminology is also dominant in Canada. But maybe they just humo(u)r us by using our "wholesome" terminology when we're around and secretly use "crotchety" terminology when they're by themselves and with everyone else. – phoog Sep 07 '22 at 08:18

-

-

@CarlWitthoft you can have a clef in any position you like if you're going to get pedantic – OrangeDog Sep 08 '22 at 20:43

-

It is indeed a breve - twice as long as a semibreve, which is the 'standard' length of note needed to fill a bar of 4/4.

Ironically, it was the shortest note used long ago - longer ones, such as the longa were in constant use. Now hardly ever used, as the time signature would need to be 8/4 at least. I say at least, looking at the example, which appears to have even more notes preceding it within the same bar. Changing the tempo of a piece would obviate use of breves, so their use has declined to almost nothing.

- 183,051

- 16

- 181

- 444

-

1Originally, it was the shorter of only two durations, whence the names "long" and "short." Only later were maxima and semibreve added, and it was a long downhill ride from there. Good point on the preceding notes without a barline; it's a bit puzzling. Up until Brahms, at least, it was not unusual to write pieces "alla breve" (with C-slash time signature) but with four beats in a measure, so 4/2 instead of 8/4. I expect that 4/2 is much more common than 8/4, at least in that period. – phoog Sep 07 '22 at 08:20

-

Also, in the original context, a breve could be half as long as a longa or one-third as long, though it makes more sense to say that a longa could be composed of two or three breves: both durations could be found in the same piece of music. The 3-breve long was called "perfect," meaning "complete," and the other "imperfect," meaning "incomplete." When shorter durations were invented, they too could be perfect or imperfect depending on context. When this became confusing, people started indicating perfect notes with ... wait for it ... a dot placed after the note. – phoog Sep 07 '22 at 09:09

-

@phoog - so basically, a longa was longa than a breve! 'When this became confusing' - probably the very first time it was used, I'd say. – Tim Sep 07 '22 at 10:12

-

@phoog - Now I'm wondering when double-dotted note notation was first made to mean "note is 1.75 times as long as indicated". – Dekkadeci Sep 07 '22 at 10:26

-

@Dekkadeci good question. It's probably after the mensural two- or threefold ambiguity disappeared, undotted notes could only ever be divided in two (I think shortly before the regular use of bar lines arose with the development of meter around 1600), and the dot came to be seen as "add one of the next smaller value" or indeed "extend this note such that the following note is halved in value." Then the double dot follows logically. I would guess this happened in the very late 17th century or early 18th. – phoog Sep 07 '22 at 10:45

-

@phoog - I like the concept (single dot) as 'add one of the next smaller note'. Might make more sense to some than 'add half the note's value'. Nice one! – Tim Sep 07 '22 at 10:50

-

@Tim you'd think it was confusing from the start, but there were rules that make it less confusing than you might expect. Something like "a single breve between two longs causes the preceding long to be imperfect." So (long=L; breve=B) L-B-L-L-B-L works out in modern notation to (crotchet=C; dotted crotchet=DC; quaver=Q) C-Q-DC-C-Q-DC. – phoog Sep 07 '22 at 10:51

-

A lot of music from that time period did not have bar lines at all, so there might not be any worry about it fitting with the same bar... – Darrel Hoffman Sep 07 '22 at 18:12

-

https://music.stackexchange.com/questions/40487/why-is-the-longest-note-value-still-in-common-use-called-a-breve-when-breve – qwr Sep 07 '22 at 19:34

-

I think it's worth noting that it was common to sing many syllables on a single note. When singing a psalm, for example, one might put all but the last few syllables of a line on a longa, then the last few syllables on a breve. Modern practice would be to write out a bunch of quarter, eighth, and sixteenth notes to show the rhythm of each line, but since different psalms have different numbers of syllables on each line, that would require writing out different music for each instead of being able to have a single piece of music to which all of the psalms could be sung. – supercat Sep 07 '22 at 23:03

-

@supercat - I remember (vaguely) singing psalms in church choir in the '50s, and yes, most of a psalm was intoned on the same note, although the rhythm was somewhat denoted by the natural rhythm of the words. Hymns would have certain numbers dedicated to them, representing the syllables for each line. Don't know if psalms had, or could have had, the same concept. – Tim Sep 08 '22 at 06:10

-

@Tim: The rhythm of psalms would be dictated by the rhythm of the words *but generally not expressed in musical notation*. The length of a longa would likewise be dictated by the amount of text to be sung. "The lord is my shepherd; I shall not" may be three as long as "want", followed by a breath of comparable length, while "Thou preparest a table before me in the presence of mine enemies: thou anointest my head with oil; my cup runneth" would may be seven times as long as "over", even though in both cases the first part of the line would be a longa and the second part a breve. – supercat Sep 08 '22 at 14:53