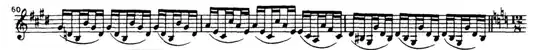

One would think of this measure as G♯ major because the notes literally spell the root, third, and fifth of a G♯-major chord: G♯, B♯, and D♯.

Furthermore, this is ultimately what the music has done. Les preludes begins in C, then it moves up a major third to E major. Then, this music in E major moves up another major third to G♯ major, albeit briefly.

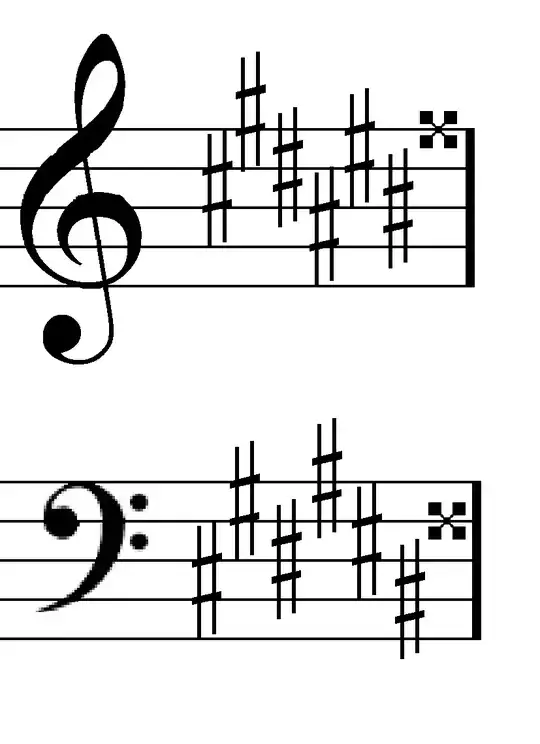

The article you cite is a bit poorly titled. There definitely is a key of G♯ major, but seeing the key signature of G♯ major is relatively rare. So rare, in fact, that we don't even agree on how these "theoretical" key signatures should look; see Where do the double accidentals go in "theoretical" key signatures? But the logic of these keys existing is very real.

As for it being easier to think of as A♭ major, that's just a practical issue: it's easier to think in a key that only has four accidentals than one that has eight sharps spread out across only seven notes. Pitches like B♯ (the third of G♯) are pretty rare compared to something like C (the third of A♭), a pitch that string players have played thousands upon thousands of times in their lives.