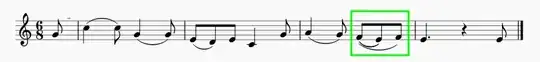

What is this (in the green rectangle)? To me it looks like 2 legatos. How do I play it on the violin?

It's the beginning of the 15th piece, "A-hunting we will go", from the Doflein Method, Volume III.

What is this (in the green rectangle)? To me it looks like 2 legatos. How do I play it on the violin?

It's the beginning of the 15th piece, "A-hunting we will go", from the Doflein Method, Volume III.

[Disclaimer: I'm going to give this a more thorough and serious answer than a short tune in a method book might warrant, since the same issues appear in larger pieces. I think what I'm about to say is true even of this example, though.]

For many instruments, like piano or winds, slurs are only about articulation. For bowed string instruments, though, they communicate something extra: they affect the direction that you physically move the bow. Because of that, sometimes we see slurs for one reason and sometimes for the other. Looking at the first measure, think about the "slurs" between the first two Cs (really, it's a "tie" when it's between the same pitch). For violin, the most basic meaning of slur is "keep your bow moving in the same direction as you change from this note to that." But if you took that literally, there would be nothing to mark the start of the second note; you would wind up playing a single dotted-quarter C. So instead, you articulate the second note by interrupting the bow slightly. It's up to you and your interpretation to decide how much; is it a full stop? Just a slight slow-down? How abrupt is the stop and the start? (The same idea is sometimes indicated by using no slur but printing two down-bow symbols over the first pair of notes and two up-bows over the next pair. And, although this interrupted bowing is the only reasonable explanation for these ties, it's usually notated by adding an expression mark like a dot or dash to one or both notes under the slur.)

In deciding these questions, let's figure out whether the slur is there for expressive reasons, as an articulation, or for is there to control the direction of the bow. Why would we need to control bow directions? Why care about up bows vs down bows at all? Well, it's easier to put a stronger emphasis on the down bow; our arm is moving (more or less) with the force of gravity and its own dead weight; the stroke starts closer to the frog and therefore has the physical advantage of leverage. There has been a tradition of putting the "strong" beats of the measure—especially the first, the downbeat—on a downbow. This so-called "rule of the downbow" is especially applicable in baroque music; here's a good explanation from (my friend) David Wilson.

Although he talks about Georg Muffat there, this principle of "adjust the bowing as necessary to put strong beats on downbows" is evident way before Muffat, in the earliest of violin treatises by Francesco Rognoni in 1620. Even in music from later time periods, the principle is still evident. So, for instance, it assumed that the eighth note pickup in this example is up-bow, so that the next downbeat can be down-bow. If you continue alternating bows through the passage, you arrive at the A, the third downbeat, on a downbow. If you then deleted the slur that spans "F-E-F," leaving only a two-note slur and making it match the eighth notes of the previous measure, then the final downbeat would come out up-bow.

I think we can conclude that the two-note slur is present for expressive purposes: if bow direction were not a concern, we would bow these eighths the same as in the previous measure. And the three-note slur is present for practical purposes of bow direction. So as you articulate it, you should do your best to make it sound exactly the same as if you had changed bow direction on the final F.

It's worth noting that there's no mention of a separation in the slur that starts that measure, the A to G. This makes this sustain stand out in the phrase as the only slur longer than a quarter note; in fact, the "slurs" in the first measure might be even more separated than if we had changed bow direction on every note. The rhythm of the sustains come out as, to make up a vocalization:

"di daa, di daa, di doodle di da; di doooooooeee doodle di daaa."

(By the way... is this a good bowing? You're certainly free to editorialize it as you want. And if this were a baroque text, I would delete the "hooked" slurs in the first measure and embrace a "strong-weak" bowing pattern for those quarters and eighths. But since it's a method book, and presuming you're a student, it's best to take it at face value and do what it says for the moment.)

The two slurs in the green rectangle show two different things.

The slur from F to E is a legato slur that indicates how to phrase this bit, the other slur indicates that you continue with the bow stroke in the same direction.

The two slurs in the green rectangle show two different things.

The slur from F to E is a legato slur that indicates how to phrase this bit, the other slur indicates that you continue with the bow stroke in the same direction.

It works this way:

If you start from the beginning with an up-bow stroke on the up-beat on the note G then you will arrive with an up-bow stroke on the F in the green rectangle. Here you play F-E with up-bow stroke then stop the bow and then continue with up-bow stroke on the last F. After that you will arrive with a down-bow stroke on the E that ends the phrase.

Thus the notes in the green rectangle will be played witrh a phrasing that is similar to the phrasing in the first part of bar 2 although the bow strokes are different.

¤ ¤ ¤

15th of August: Here is an elaboration inspired by a comment added by @gidds :