As you mentioned in your question, there is little documentation about this phenomenon. Therefore I will preface my answer by saying that it (my answer) is speculation based from what knowledge I have of acoustics, historical performance practice, and literature.

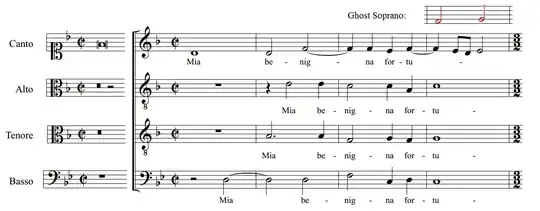

I am not aware of any piece of music that was conceived with the intention of being constructed with or around the ghost-voice phenomenon. Considering that it is most prominent using just intonation, we could then surmise that musicians during the Renaissance and early Baroque periods most likely experienced ghost-voices since secular musical material consisted dominantly of motets and chansons and Just Intonation was the primary tuning system.

That said, since the tuning system itself was different (and the notation stayed the same, generally speaking,) that would mean that even if Renaissance motets were sung in a contemporary setting, they would be sung and tuned in an Equal-Temperament system. Therefore, to properly experience this phenomenon in the literature, you would have to time travel approximately 500-700 years in the past in order to hear the music in its proper (original) temperament.

Why is this important? Why does it work best with Just Intonation?

The answer to this is two-fold: the overtone series, combination tones, and overtone singing.

Okay, maybe it's three-fold.

In Just Intonation, the emphasis is on tuning perfect octaves and fifths as they are the easiest interval to hear apart from the unison. These intervals were tuned "perfectly" - regardless of their proximity to other, less important intervals.

Okay, so why does that matter? The answer is: Organs.

For their lowest pitches, pipe organs actually make use of their own phenomenon called combination tones in which two pipes of equal length will vibrate at the same pitch adjacent to one another. The additive combination of their frequencies / wavelengths produces a perceived sound an octave lower.

Singing a perfect fifth or a perfect octave in Just Intonation allows combination tones to flourish as they are tuned to small whole integers and not a fractional ratio like Equal Temperament. If you follow the link on combination tones, you'll see that they can even produce multiple perceived pitches as the "sum" or the "difference" between the two pitches.

Therefore, when you experience a "ghost voice" in a piece of music, it is the result of combination tones highlighting upper partials in the overtone series - creating the illusion that more pitches are being produced than are physically being produced.

Other examples of this type of phenomenon may be found in Tuvan Throat / Overtone Singing in which individuals manipulate their vocal folds to reinforce particular harmonics - frequently often able to produce several pitches simultaneously. These are quite a bit different than combination tones, but it is part of their performance practice.

From Tuva, cases may also be made for Tibetan throat singing and perhaps even Russian Orthodox singing technique as well. So, while it is difficult to produce documentation or literature in the Western musical tradition concerning "ghost voices" examples of this phenomenon can be logically considered to have existed in historical practice and in Eastern cultures around the world.

Hope that helps.