This is a fascinating question, and although I don't have a definite source that says this or that, I believe I've triangulated the data as best we can. For simplicity's sake, I'll refer to some entries in the Harvard Dictionary of Music.

The entry for dotted note isn't all that helpful, but the entry for tie tells us that "[t]he advent of the tie coincides with the advent of the bar line." When considering the bar line entry, we read that "the earliest [instance is in] Faenza, Biblioteca comunale, 117, from ca. 1400."

With this, let's assume that the tie appeared, at the earliest, around the year 1400.

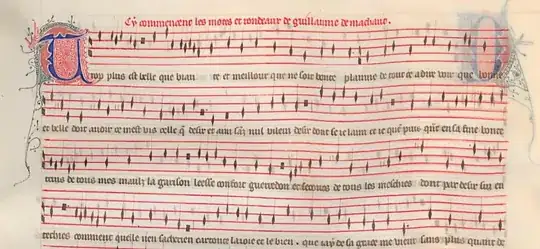

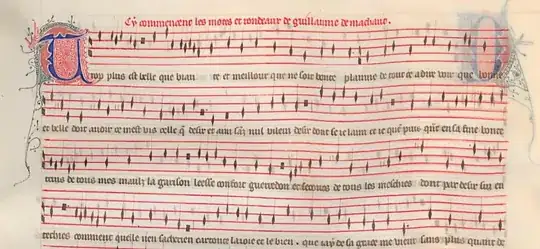

The earliest dot notation that I know of is from Machaut; I found this example in his manuscripts from MS E, 131r:

Machaut, however, died in 1377, meaning that these manuscripts would have been dating from sometime before this date.

Thus with the earliest appearance of the tie being "ca. 1400" and definitive evidence of dots appearing, at the latest, in 1377, we can assume the dot appeared first.

There's of course some wiggle room here with the meaning of "ca. 1400," but I think we're relatively safe to assume that the dot preceded the tie. Further evidence of this is that Machaut was operating in the ars nova, a tradition connected to treatises from ca. 1320 of Jehan des Murs and Philippe de Vitry. (There's also an interesting national connection: this is a French tradition, but the appearance of the bar line in the Faenza manuscript is Italian!)

With all of this said, the musical idea of elongating a prior note by some amount long precedes the visual notation of the dot and tie themselves. But these particular symbols were made necessary as rhythmic notation evolved from rhythmic modes through mensural and proportional systems into something like what we have today.