I am installing all new electrical wiring in an all new home. I would like to know whether it is better to run my lighting circuits with 14/2 wire from the panel to the switch then 14/2 wire to the lighting fixture or should I run 14/2 wire from the panel to the lighting fixture then use 14/3 wire from the fixture to the switch?

-

So you are putting the lighting on separate circuits (15 A) from receptacles? – Jim Stewart Aug 27 '17 at 10:38

-

You drill fewer holes with plan B. Whichever you choose be consistent throughout. – Tyson Aug 27 '17 at 13:57

-

@retired master electrician thank you all so much. I really appreciate each one of you taking the time to give me such awesome and equally different yet great insight. . thank you again... – cdguitarok Aug 28 '17 at 12:09

-

@ThreePhaseEel could only comment to 1 of you per comment but I'm grateful enough to make enogh comments to be sure all who shared their tim and knowledge with me gets a proper thank you – cdguitarok Aug 28 '17 at 12:13

-

@Harper above comments apply to you just as sincerely – cdguitarok Aug 28 '17 at 12:15

-

@John Deters please read above comments as they are directed to you also. thank you guys I'm getting ready to go in and meet with owner and now have awesome confidence with the multiple scenarios I can paint for him. You all and this site made my day, week, month...seriously thank you – cdguitarok Aug 28 '17 at 12:23

4 Answers

Be practical - not rigid

Only you know your home's layout. Either go to "switch first" or "lamp first" depending on what is most practical based on the "lay of the land".

For instance, having arrived at a lamp, the nearest thing may be another lamp in another room. OK, go there, and then to its switch. And behind that wall is a third switch going to a third lamp. Etc. Power-S=L-L=S-S=L for instance.

Also, you are allowed to "tee" in any junction box (remember junction boxes must be always accessible and cannot be covered over by any part of the building, other than lamps and cover plates), so if branching a "tee" off an existing circuit run makes sense, go ahead and do it.

Generally you use /2 cable. You need /3 cable between a switch and all the lamps it controls -- unless the lamp(s) are at the very end of the string.

Avoid the too-many-wires trap - change routing

If you have 3-way switches, things get more complicated. You can easily reach a point where you need 5 wires (hot, neutral, switched-hot, 2 messengers). /5 is hard to get, and you're not allowed to parallel cables to make one. On these, slow down, graph it out and possibly change your topology - for instance make the other 3-way a dedicated branch with a /3. Or use smart switches. Or change wiring methods to conduit and use as many single THHN wires as you need.

For instance if your layout is Power-3-L-L-3-receptacle that's impossible without /5, so you do it this way

Power-3-L-L-receptacle

|

3

and only need /3. Even if the /3 cable between the switches is laid right next to the lines to the lamps, it's not considered parallel because it doesn't connect electrically.

Other tricks

Standard practices in house design are a compromise to save money. No need for you to compromise, here are some things you can do better.

Run 20A (12 AWG) circuits even where not required -- though this is a lost cause with lighting, as with efficient LEDs, all the lighting in your home won't add up to 12A.

Put overhead lights in every room - the new thing of "don't install any overhead lights, just switch a receptacle" isn't trendy, it's just cheap. And it prevents use of dimmers. EMT's and other first responders will thank you.

Kitchens require 2 circuits for countertop receptacles, but your chef would love to have as many as possible. Most kitchen appliances which use heat use 1500 watts of power. The max for a 20A circuit is 2400W, so it can't support two. You can imagine in a 2-circuit kitchen, that will drive a chef nuts. Can't run the skillet, waffler and toaster at the same time. You can fix that by running plenty more circuits, and adding outlets beyond what is required, e.g. putting 2 dual receptacles where one is required. Also think about where people like to charge their phones.

Either use GFCI receptacles, or use plain receptacles with GFCI protection upstream (e.g. at the breaker panel). To extremes: split each kitchen receptacle and run /2/2 cable (hot hot2 neutral neutral2) to the panel, and punch them down to two GFCI breakers. That means each socket gets a dedicated breaker.

If you put the refrigerator on a dedicated circuit, that assures nothing else will trip it. I hate the idea of GFCIs on a fridge circuit, as it only makes this trip problem worse. Assure it stays dedicated by bringing it to a single receptacle (1 socket not the usual 2). If you expect to have a chest freezer, also provision a dedicated circuit for that.

Same with extra circuits in bathrooms - hair dryer and curler and little electric heater!

Speaking of bathrooms, it's forward-thinking to lay conduit between the switch area and the overhead light/fan/heater/etc. That way you don't have to sweat how many wires to put there, you can just pull what you need.

Ditto anywhere you put a ceiling-fan box.

Get the biggest panel possible. The size of your service panel is no place to save $50. We get lots of "My panel is full, help" questions but never a "what do I do with all these panel spaces?" problems. Aim for the panel to have 50% spare spaces when you are done.

Use subpanels to avoid long hauls of many parallel Romex cables. A friend has a long house with his panel on one end, not much in the middle, and a cluster of bedrooms and bathrooms on the far end. That's the perfect application for a subpanel, and a subpanel is an easy/cheap way to add a lot more spaces: instead of an expensive 60-space panel, have a 40 main and a 30 sub. You could even feed a subpanel with a GFCI breaker, conferring GFCI protection to every circuit in it, and saving money on individual devices.

Speaking of refrigerators/freezers... Think forward about which loads would be most urgent for an emergency generator or solar-panel/battery/inverter system. Put these in a separate subpanel, and leave physical space for a changeover switch, even if you don't install it.

If the load is just refrigerators, gas furnace and a few lights, I would get a subpanel that supports a simple manual interlock, fit the generator-side breaker, and put all the loads on one pole. Then on the generator feed breaker, connect that pole to a 120V inlet socket. That would be cheap/easy. Then, with an extension cord and a small Honda generator, you could get critical loads lit without too much work. You don't want to have no protection at all while you decide on whether to commit to the expensive, complicated rigmarole of a whole-house generator setup.

- 276,940

- 24

- 257

- 671

Since newer codes require a neutral at the switch box I would say run to the switch first. Also it would cut down on the installer having to make a decision as to whether or not to use 14/2 or 14/3. I like to keep it simple. There is really no real savings as far as I know. The problem is trying to get the installer to do it that way since old habits are hard to break.

Good luck

- 13,041

- 10

- 31

Being penny-wise now can be quite pound-foolish later

Most residential wiring practice is meant to be one thing and one thing only: CHEAP. While doing it right may be more expensive now, it will pay off down the road in terms of longevity, expandability, and maintainability.

Go BIG or go home!

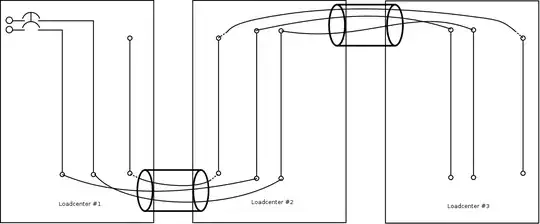

That said, let's move on to more specific points to address, starting at the panel. You'll want the biggest panel you can get in terms of slots (Siemens makes 54 slot units, and Square D and Eaton both make 60slot panels -- if you're really in "cost is no object" land, Square D also makes an 84 slot NQ but that's squarely in commercial panelboard territory as it requires a 20" wide box). In fact, for a new house, I'd recommend two of those 54 or 60 slot panels, daisy-chained using subfeed lugs, as depicted below -- that way, double-stuff breakers will stay a thing of the past.

NM is for chumps, and today's MCI-A cables are like BX, just better

Moving out from there, the first question you should ask yourself is "why is NM a thing?" The answer is obvious -- it's CHEAP. While individual THHN wires in metal conduit (normally EMT these days) is the Cadillac of wiring methods, it's also quite laborious, especially if you aren't good at pulling wires -- it's still useful for heavier branch circuits or in providing an explicit provision for future expansion, though, so we'll come back to it.

"What about BX? Shouldn't that provide the best of both worlds -- low cost and easy installation, while still surrounding the wires with metal to protect against damage and faults?" The answer to this question is almost -- BX evolved into today's type AC cables, which while better than NM, are still not the ideal product as their grounding path is undersized. Type MC cables were developed later on, and provide a full-size grounding wire, but don't incorporate the armor into the grounding path; both types also suffer from messy assembly due to paper wraps or plastic tapes getting in the way.

Enter the recent development of type MCI-A cable -- this is a cable that is similar to AC and MC, but uses a full-sized bonding wire in intimate contact with its metal armor, providing superb grounding performance, easily on par with conduit systems. The fine folks at AFC even developed a MCI-A cable that dispenses with the assembly tape altogether. Combine this with the availability of MCI-A connectors that are snap-in/snap-fit (Arlington's Snap2It line, for instance), and you get a system that's not that much more labor intensive to install than NM, while providing all the advantages of an armored cable system.

There will still be places you'll need to revert back to conduit, though. MCI-A cable, as of this writing, is only available in branch circuit sizes (14-10AWG, 2-4 wire + ground, as well as two-circuit and three-circuit cables in 12 or 10 AWG equivalent to 12/2/2 or even 12/2/2/2 cable), so your feeders will need to be in conduit if you have subpanel plans -- this is wise anyway though to allow for future upgrades. Likewise, your 40 and 50A branch circuits will need to use something other than MCI-A -- I'd use EMT + THHN for those, as they are few in number and generally more direct in run than smaller branch circuits. Another place where future upgrades are good is whenever provisions for a fan such as a ceiling fan or bath fan are made -- conduit from the switch box to the fan box allows for future wiring upgrades. Last but not least, outdoor branch circuits and feeders are another place where pipe-and-wire excels as Schedule 80 PVC conduit lasts essentially forever underground.

Layout matters...

You'll want to think up-front about how you lay out wiring to avoid the "too many wires in a cable" problem, as well as other issues. Separating lighting from receptacles helps with this, for one, and also helps massively in making sure that accidents don't turn out the lights on you.

Another good strategy is to provide each room with its own receptacle circuit and its own lighting feed straight from the panel, instead of dropping receptacles and lights off of whatever branch circuit is handy -- this goes hand-in-hand with giving each room a single, central place where all the switches/switch loops, lighting connections, receptacle feeds, and homeruns come together, which is practical nowadays that we have 5" and even 6" square boxes to play with, as well as dual-circuit (/2/2) cables. While this may sound like overkill breaker-wise, you don't need to provision an entire 15 or 20A lighting circuit for one room -- you can splice multiple lighting feeds together into the panel then pigtail the splice to a breaker to "multiplex" lighting feeds onto a single breaker without having the lighting circuit running all over the house. (Think of it like the difference between old Thinnet bus-style Ethernet and a modern switched Ethernet network.)

Likewise, running double-circuit cables for kitchen branch circuits means that you can break both tabs on your kitchen counter receptacles, then have two full 20A circuits available to you at every kitchen countertop receptacle. Of course, this requires the use of DFCI breakers at the panel to protect this, instead of an AFCI in the panel and a GFCI receptacle.

Speaking of receptacles (and switches), don't cheap out! A good specification-grade or heavy-duty industrial-grade receptacle or switch only costs a few bucks (or maybe a dozen-odd bucks) more than a cheap builder-grade receptacle or switch, but has proper screw-clamp backwiring instead of backstabs, and will last far longer as well no matter what abuse it sees down the road. (I've seen a few broken insulating faces on what I can only presume were builder-grade receptacles.)

...but so does installation technique

Of course, even the best parts can be ruined by bad installation technique. First off, there's the matter of torque. While most household screws are adequate at "good n' tight", electrical connections (especially to aluminum wire) are like Goldilocks -- too tight will set you up for failure just as reliably as too loose will. As a result, the 2017 NEC introduced a requirement in 110.14(D) that torque tools (such as a torque screwdriver or inch-pound torque wrench) must be used to tighten connections to the manufacturer's specified torque. Furthermore, even if your jurisdiction has not adopted the 2017 NEC, you can write it into the contract with your electrician that they follow 110.14(D) in the 2017 NEC -- the Codes allow one to take a degree of AHJ power into their own hands contractually like that, and it can be useful when newer Code editions have good ideas in them, but your jurisdiction hasn't caught up to adopting the new edition yet.

Likewise, ensuring boxes are rigidly mounted and stay free of contaminants (drywall mud and paint are common culprits) can help prevent future issues -- a wobbly box can aggravate bad connections, and stray paint or mud splatters contribute to wiring identification headaches down the road. Fortunately, keeping the splatters out is easy: simply stuff wads of newspaper into the boxes post-rough-in-inspection before the drywall and paint crews go through.

- 79,142

- 28

- 127

- 220

If money is truly no issue, consider installing home automation capable switches to control your installed lighting. This way you can use 14/2 to get to the primary switch, 14/2 from the primary switch to the light fixture(s), 14/2 to get power to the remote switches from the nearest outlet, and then use Z-wave or Insteon to communicate from the remote 3-way or 4-way switch locations without needing to add travelers.

But once you start pricing out home automation switches, you may discover that money might be an issue after all.

- 111

- 2