I'll give an example that isn't from a world championship match, and isn't recent either. In fact, it doesn't even have an en passant capture in it. (Bear with me.) It does have a world champion playing in it, though, and more importantly, I hope it illustrates the following: even when no en passant capture actually occurs in a game, the fact that it is possible might be playing a very big role. This is not entirely unrelated to the old chess saying, "the threat is stronger than the execution."

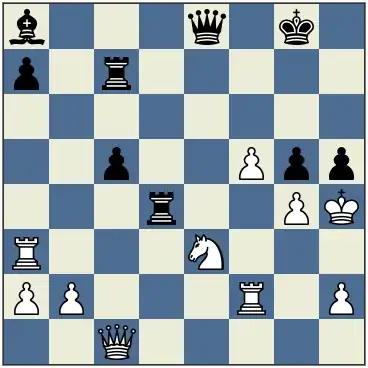

In the game Alekhine - Yates (London 1922), we have the following position after black's thirty-first move:

[FEN "r3r1k1/2R3p1/2R1p2p/3pNp1P/p2P1K2/Pp2PP2/1P4P1/5b2 w - - 0 31"]

1. g3 1... Ba6 (1... g5+ 2. hxg6) 2. Rf7 Kh7 3. Rcc7 Rg8 4. Nd7 Kh8 5. Nf6 Rgf8 6. Rxg7! Rxf6 7. Ke5 7... 1-0 (7... Rff8 8. Rh7+ Kg8 9. Rcg7#) (7... Raf8 8. Rh7+ Kg8 9. Rcg7#)

Alekhine has boldly played his king forward with the idea of infiltrating the black position via e5. On the previous move, Yates had attacked his g-pawn with 31. ... Bf1 and Alekhine replies simply with 32. g3 to keep the pawn safe, ready to get back to business after that. Looking at the position, we can see that if Alekhine didn't have the en passant capture at his disposal, then Yates would be able to checkmate him with 32. ... g5. But since the rule is in effect, Alekhine's king is actually perfectly safe, and in a strong position to help his other forces attack.

Now Alekhine didn't have to play 32. g3 setting up this "pseudo-mate" possibility. But still the point is that the white pawn on h5 and its en passant threat plays a big part in Alekhine's suffocating clamp on the black position, and his successful invasion. Yates resigned only a few moves later, with Alekhine's king delivering the final blow on e5: 32. ... Ba6 33. Rf7 Kh7 34. Rcc7 Rg8 35. Nd7 Kh8 36. Nf6 Rgf8 37. Rxg7! Rxf6 38. Ke5 1-0.

Yates must lose his rook, because if either rook moves to f8, Alekhine has mate in two with 39. Rh7+ Kg8 40. Rcg7#. To reiterate the larger point:

Many potential en passant captures that never actually occur, because the mere possibility of it discourages the other player from ever making the two-square advance in the first place, still play a major role in the game. This aspect - the most effective en passant is perhaps the one you never see - is one reason why, superficially, the en passant capture might seem like a less important/significant feature of chess than it actually is.