After 1. e4 e5 2. Nf3 Nc5 3. Bc4 Bc5 4. d3, you could continue with 4. ... Nf6 and aim to follow this up with an immediate 5. ... d5 if you want to open the center. For instance, play could proceed with 5. O-O d5 6. exd5 Nxd5 7. Nc3 Nxc3 8. bxc3 O-O, and you would have a rather open game.

But White need not allow this, and would likely instead play the natural 5. Nc3, bringing us into the Italian Four Knights, and stalling the idea of a ... d5 push by Black. The thing here is, White has concentrated a lot of attention on the d5 square precisely so that it is difficult for Black to play this freeing ... d5 move, which would immediately relieve Black of any hint of a cramped position. Black would now need to do some prep work in order to make this central advance happen, if that is what she wants. She might play e.g. O-O, d6, Be6 first, so that the move ... d5 is properly supported. Of course White will be playing his own moves in the meantime, and if he wants to keep things quiet for a while, he can often make it so that Black can only upset this at her own peril. But with the sort preparatory moves I've indicated, ultimately White cannot prevent you from getting ... d5 in and opening things up in a safe way.

I'm going to speak below to something more general that your question brings to mind, as it might be useful. Feel free to ignore if not, though.

One point worth making here is that some games just will be, to use your words, more "slow and boring" than others will. It's all well and good to prefer more open, dynamic, active games. But it can be a bad idea to insist upon a "faster" and more open game if doing so means recklessly putting oneself in danger, and it often can mean just that. An alternative approach (and one that will go far in leading you out of your beginner phase) is to try to see the slower, more closed phases of your games as not so boring after all, and realize that a lot can be going on "under the hood," so to speak. (Besides, the moves you play during "slower" phases are crucial to your success/failure once the position does open up.)

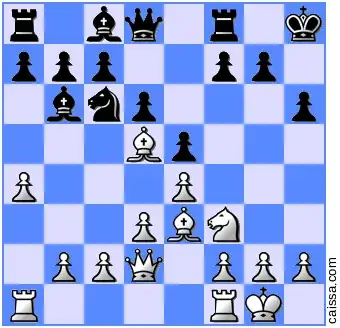

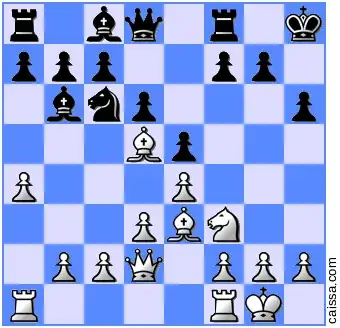

To illustrate this idea (very lightly), suppose our game proceeded, after 5. Nc3, by 5. ... h6 6. Be3 Bb6 7. O-O O-O 8. Nd5 d6 9. a4 Nxd5 10. Bxd5, and Black, desperate to open the game via an ... f5 push, plays 10. ... Kh8 in order to get out of the pin from the bishop on d5. White responds with 11. Qd2, and we have the following position:

So far, a pair of knights has been exchanged, but all the pawns (and everything else) are still on the board, and things have indeed been rather closed and quiet. This doesn't mean interesting things haven't been happening, and in particular, White has developed his pieces well so that it still isn't a good idea for Black to try and open the position without further preparation: 11. ... f5? is met harshly by 12. Bxh6, which wins a pawn because of 12. ... gxh6?? 13. Qxh6#. Instead, Black could play 11. ... Bxe3 12. fxe3 f5, and she has finally achieved the kind of opening of the position that she has been after.

My main point: sometimes one simply must be patient in chess, or else accept the consequences. Wanting to blast open the position only because, well, you always want to blast open the position, is going to lead you into a lot of trouble and missed opportunities. Sometimes you will find yourself in positions where it would be to your objective advantage to keep the position closed (maybe your opponent has a very cramped position that will ultimately prove fatal), but if you were to always blindly favor opening the game up, you would miss out on that kind of winning approach - or worse, you'll open yourself up to the kind of punishment illustrated above - and you will ultimately have worse results than you rightly should. Just something to keep in mind as you continue to explore the game.