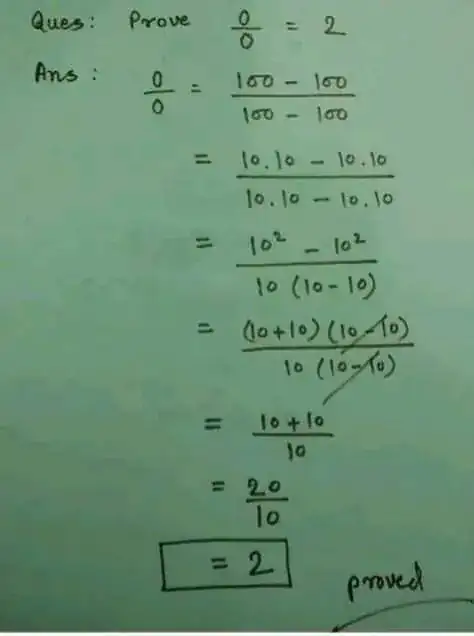

As you've noticed, compared to +, - and ×, division is special. There are three schools of thought around questions like this:

0÷0 is undefined

Whenever you try to define it, you end up with a contradiction. Therefore, the division operation is undefined for 0 and 0.

x÷0 is a multi-valued function with all possible values

For every value, you can prove that value is equal to 0÷0. Therefore, it is equal to 0÷0.

What is division, anyway? a÷b means to separate a into b equally-sized groups; when the denominator is 0, there are no groups, so every statement about the group size is vacuously true.

Since it has all values, we don't have a contradiction when we say it has a particular value. Narrowing a multifunction down to a single value is not always a valid thing to do; if you've got a contradiction because you discarded solutions, all that means is you made an algebra mistake.

Here's a simpler example of such an algebra mistake: I'll "prove" that -6 = 0.

- -3 × -3 = 9

- Square-rooting both sides, we get √(-3 × -3) = √9

- √(a × a) = a, so √(-3 × -3) = -3

- √9 = 3

- Therefore, -3 = 3

- Subtract 3 from both sides: -6 = 0

To resolve this issue, we have to either treat define the square root as the positive square root (so √(a × a) = |a|), or treat the square root consistently like a multifunction (√(a × a) = a or -a):

- -3 × -3 = 9

- √(-3 × -3) = {-3, 3}

- √9 = {3, -3}

- Therefore, {3, -3} ⊥̷ {-3, 3}

0÷0 is defined as having a specific value

Sometimes, it's inconvenient to make division anything other than a total function, so we just define 0÷0 as something, usually 0 or 1. This does mean there are a few algebraic tricks we can't do any more, since they'd lead to a contradiction if we tried to do them on 0÷0.

These different definitions of 0÷0 affect the validity of cancelling out the (10 - 10). Instead of viewing that as a single operation, it might be clearer to think of it as three operations:

- ac ÷ bc = (a÷b) × (c÷c)

- c÷c = 1

- (a÷b) × 1 = a÷b

If these three claims are true, we can "cancel top and bottom". We can prove the third equality quite easily, but the second and (to a lesser extent) first equalities depend on the definition of 0÷0!

- If 0÷0 is undefined, c÷c = 1 iff c≠0. But, c = 10 - 10, so it's not valid to cancel.

- If 0÷0 is a multi-valued function, then 1 is always a valid solution for c÷c. However, if c=0, there are other solutions too. Discarding some of those solutions is an extra premise in your argument – or, if you'd prefer, a sloppy argument-by-cases –, and you need to keep that in mind if you end up with a contradiction, because that doesn't necessarily tell you that your original premise was faulty.

- If 0÷0 is defined as having a specific value:

- If c÷c = 0, c÷c = 1 if c≠0, otherwise 0. Following your proof with this rule, we conclude that 0÷0 = 2×0, which isn't a contradiction.

- If c÷c = 1, then the second rule is always valid, but ac ÷ bc = (a÷b) × (c÷c) is only a valid operation when c≠0 or a=b. (This is why I don't like defining 0÷0 = 1; I like the first rule!)

None of these definitions lead to a contradiction.