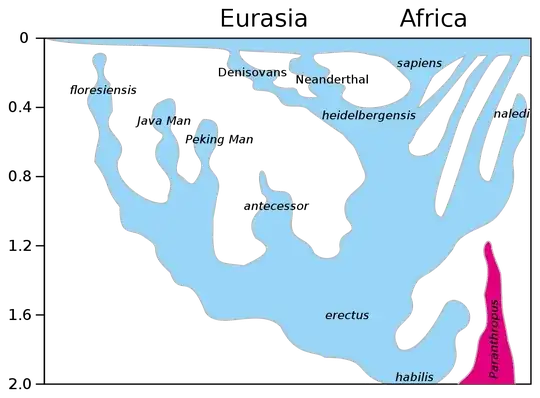

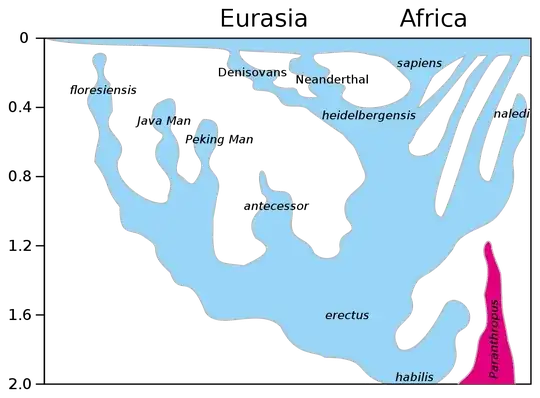

I would say the assumptions here are wrong-headed in several ways. Homonid speciation, was driven by isolation related to climate conditions. And when they reconnected, they interbred.

From Human Evolution: Evolution of the genus homo on Wikipedia.

From Human Evolution: Evolution of the genus homo on Wikipedia.

There are some more maps and discussion relating to the convergence of the hominid species here: Can you explain clearly the difference between race and ethnicity? Humans are an exceptionally undiverse species, because of the small population after the Toba bottleneck, and limited admixture (3-5% of genes) from other hominid species. There is less variation among all humans, than within some specific breeds of dog. Skin colour is only controlled by about ten genes, and skin albedo of indigenous populations closely follows a map of humidity, and this has tended to confound our ideas about how much we vary.

The thing about speciation, is it's not a one-way street. In good times sure, homogeneity increases. But a lot of evolution is driven by punctuations in the equilibrium, like Ice Ages, mass-extinctions, volcanic eruptions. And, we are just at the beginning of a climate roller-coaster, with few indications of mitigation. 50% of species have been lost in the last century, the majority of those in the last 50 years, and the pace is accelerating. There are unknown factors like Siberian permafrost & oceanic methane-hydrate methane release, and weakening of the Gulf Stream, which could plausibly trigger huge migrations related to rising sea-levels, drought, and an unlivable mix of heat and humidity in many regions.

Failure to effectively deal with mass migrations is linked to the Fall of Rome in the Migration Period. The recent Syrian War was triggered partly by drought with no government relief, giving a sense of how conflicts may rise. We assume progress will keep marching forwards, but that ignores the record of civilisational collapse. Previous examples have not resulted in homo sapiens speciating. But now we have nuclear weapons, which could result in a multi-year Nuclear Winter, which would really radically challenge our species.

Going to Mars, will see a group of humans there face dramatically different selection conditions, like low gravity and high solar radiation, as well as substantial physical isolation, which could easily be made more complete by widespread war and civilisational collapse on Earth. A recipe for a new species to emerge.

A final point to consider is horizontal gene transfer. You might consider humans as the species that perfected 'horizontal meme transfer', mimicing cave bear claws with handaxes, persistence hunting like wolves, and wearing flippers like fish. We will also doubtless be initiating a new era, of genetic and phenotypic plasticity from intentional horizontal gene transfer, and fabrication. Our ability to do this safely is currently limited, but quantum computing is perfect for doing protein-folding calculations, which will greatly help. We might choose to create new human species, or to mix with other species.

On the more general question, is homogenisation bad?

Having variety when a collapse hits, can help at least some to survive, and it's hard to know what traits could become pivotal. Travel, and media, have tended to increasingly limit the scope cultural variation (see discussion of some changes here: Is physical attractiveness subjective?).

There are estimates that every 40 days a language dies, and language death is an accelerating phenomenon, while the fact most computer coding requires some knowledge of English, is further pushing an already widespread language as a dominant second-language. There has historically been hostility to minority languages, but the resurgence of Welsh, Irish Gaelic, and Hawaiian, are indicative of how that is changing. I would look to the impact of relearning of Ancient Greek on the Western Holy Roman Empire (luckily preserved elsewhere), the accessing of climate data from Australian Aborigine oral traditions, and what would have happened without discovering the Rosetta Stone, as examples of how losing languages could mean permanent loss of information. Losing a language tends to relate to losing a culture and it's traditions, to losing a way of seeing and relating to the world. I don't think we should be embracing homogeneity, but instead celebrating diversity.

The different cultural practices of different groups, who are in various competitions and contentions, has been a major driver of social progress. Interesting examples are, the emergence of Ancient Athenian Democracy, and the codifying of habeus corpus. I would contend that these far-reaching social technologies, provided lasting benefits to the societies that developed them and were inspired by them. We need groups trying out new ways to live and organise. But we also need the ones that suceed, to be able to transmit their new way - and while we hope that will be through soft-power, the real backstop is hard-power. NATO has codified community standards that benefit members, without reducing their autonomy, and that kind of alliance that sustains difference fortunately seems to have overtaken cultural imperialism, which China and Russia seem intent on keeping alive, but in a global minority doing so.