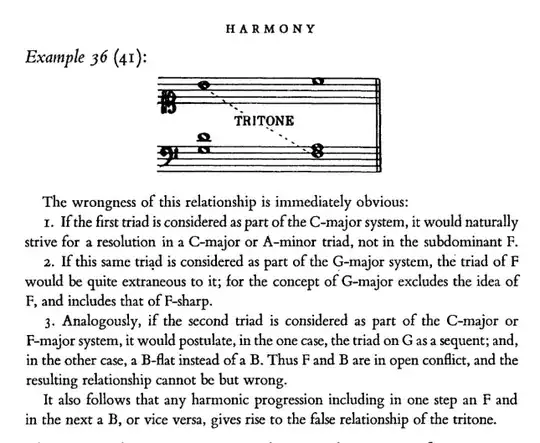

I'd like to give a historical account of this, where the question becomes "under what conditions did cross relations of the tritone become permitted?".

The wider definition of false relations comes from any perfect interval which has been augmented or diminished, although this type of false relation "of the tritone" is listed under "Mi contra Fa" by many of the older theorists, and quoted in Grove. As defined by Gioseffo Zarlino (1558) in Le Istitutioni Harmoniche (Book III Chapter 30) this includes the tritone (both in its original augmented fourth form as well as its diminished fifth form) as well as the augmented and diminished octaves.

Parallel major thirds (and parallel minor sixths) are particularly problematic because of this, and Zarlino suggests avoiding all such progressions in compositions of two voices (III.31). However, in compositions of more than two voices, he argues that just as there are in medicine "deadly ingredients which in combination with other substances are healthful", so in music, "there are intervals and relations that give little pleasure in themselves, but have wonderful effect when combined with others."

Interestingly, the outlined / diagonal tritone was more directly criticised than the simultaneous tritone in late Renaissance theory, specifically allowing for the diminished fifth as a vertical interval even in two-part harmony.

This difference in treatment between the vertical tritone and the diagonally adjacent tritone comes to the fore in the baroque - in an analysis from c. 1700 of Lully's Proserpine, vertical tritones resolve very differently from other dissonances, and at one point states that a vertical tritone "moderates the inharmonical relation" of a diagonal tritone!

Indeed, Zarlino himself is inconsistent with his own rules, including writing tritone cross-relations between tenor and bass. This appears to be related to cadences in his examples: where from a functional harmony perspective we would see dominant to tonic functions, Zarlino would see a leading tone moving to its final with an appropriate(ly prepared) dissonance over the tenor clause. Cadences with such dissonant suspensions (which at this point includes the perfect fourth) are given their own category by Zarlino, a cadenza diminuita (Book III Chapter 53).

The idea of the elaborated cadence accepting such dissonances is carried forward in late 17th century and 18th century treatises, under various names (cadenza composta, cadentia ligata). It is this contrapuntal dissonance that defines such a cadence: an admission and acceptance of dissonance (including, indeed especially tritones) in cadential contexts that we would now see as IV-V or ii-V harmonic progressions.

However, non-cadential progressions did not gain the license to be so liberal with their dissonances, whilst cadences became the "instigation and release of tension by means of dissonance" with the rise of harmony-based thinking after Rameau. As V - IV was vanishingly rare in cadences, even in "evaded" ones (now called "interrupted" cadences), older guidelines persisted from earlier considerations of tritone dissonance, and also served to "justify" the salience of the tritone's value in cadential harmony as opposed to non-cadential progressions.