Assuming the 4th edition is the same as the 3rd at this point (though the page numbers are not quite the same) you have separated the first half of what the book says from the second half.

Taken together, they just mean "the 7th note of the chord can be preceded by anything, but must be followed by the note a semitone or tone lower" (in major or minor keys respectively).

He then claims that some preceding notes are more common (and "better" in some undefined sense) than others.

There are two self-consistent ways to write about common practice harmony. One is to observe what composers wrote historically, and attempt to extract general principles from it.

The other is to assume there is some Platonic musical ideal called "common practice harmony" and prescribe the rules for writing it.

The trouble with many books (including Laitz) is that they conflate the two things, and state dogma as if it were fact. It is quite reasonable for a student who wants to learn (as compared with one who wants to get a good grade in an exam) to question almost every pronouncement in a book like Laitz, and not find a convincing answer in the book itself - because there isn't any answer except "historically, composers wrote this more often than that."

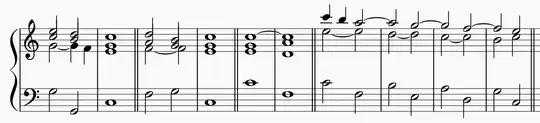

In this specific case, it is easy enough to find common practice harmonic progressions which don't follow Laitz's dogma - for example where one dominant 7th chord resolves onto another one, in a progression like this: