(I'm asking about something like this segment: 3/4 ^G,3/4 [^D3^D,3/2]

=G,3/2 [c/4C,/4] C/4 [d3/8^A,/8] G; taken straight from A Little Fight Mewsic by Homestuck)

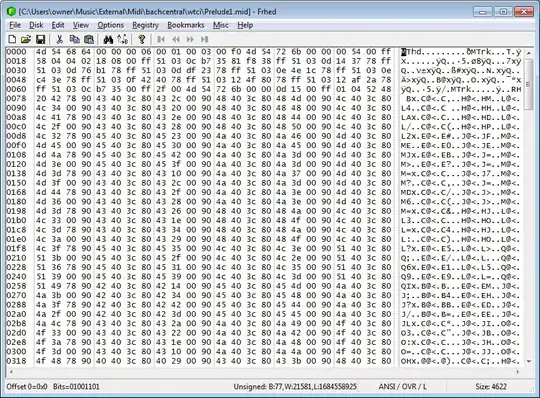

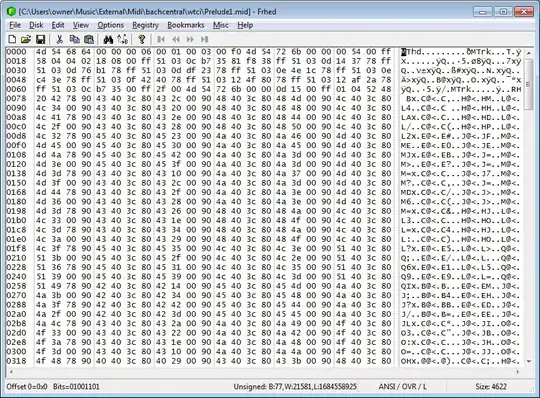

You seem to be confused about what MIDI is. I'm not sure where you got that, but the above clip is emphatically not MIDI. MIDI is a binary format, and as such, is not really human readable. Here, for example, is the opening of Bach's Prelude No. 1 in C Major from the Well-Tempered Clavier, as viewed in a binary editor. Or at least one MIDI realization of it:

What you have looks like an ASCII/text-based format. It might be something like the ABC file format (or some variant thereof), or it could be something else. But it is definitely not MIDI.

How does one actually make an MIDI file work,

One typically uses another program to export a MIDI file. These often take the form of a musical notation program, such as Musescore, Lilypond, Finale, or Sibelieus; or the piano-roll editor of a more fully-featured DAW, such as Reaper, Sonar, Logic, or Garageband.

Or else one writes their own computer program from scratch to create a MIDI file that conforms with the MIDI standard file format. One does not simply manually edit a MIDI file in their right mind.

Given the clip you provided, I do not believe your question should actually be about MIDI. However, I will answer your question anyway, from a high-level, perspective of MIDI.

as in, what determines the octave and the length of each note? How does the notation form a note correctly?

MIDI was first-and-foremost designed as a specification for controlling hardware. As such, it consists of a series of digital commands called MIDI Messages that are sent over a cable in real time. These messages typically represent performance data (such as depressing and releasing keys or pedals, twisting knobs, adjusting sliders, or varying breath pressure), and are used control a musical synthesizer -- either a hardware synth or a software synth (though other equipment such as stage lighting can be controlled as well). How the synthesizer reacts to these messages to produce sound, or other effects, is up to each individual synth implementation to determine. Some messages are also tagged with a number called a "channel" from 0-15, which I'm not going to discuss further.

MIDI files are a way of storing these messages. Each MIDI message is preceded by a corresponding time stamp, and this pair forms a MIDI Event -- a specific message at a specific time. The timestamp is actually provided as a delta-time; it gives the number of abstract units called ticks from the previous event. Converting between ticks and real time or musical time (bar, beat) can be a bit of a convoluted practice... For convenience, events in a file can be grouped into sequences called tracks. A MIDI file will then contain a header section, and some number of tracks.

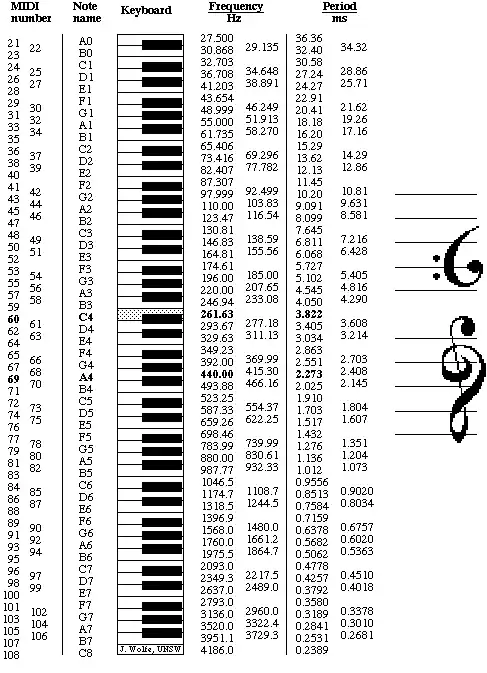

Because a musical note lasts for a certain duration, and is not a single point in time, there is not a single "note" event in MIDI. Instead, to "form a note correctly" requires two events -- Note On, and Note Off -- representing the start and end of the note. These messages each have a note number, listed in the table that Felice provided, representing their pitch including octave. The duration of the note is just all the time that happens between these two events. Since there can be any number of other events in between them, if you wanted the full duration, you'd have to add together all the delta-times of all the events after the note-on event until you find a corresponding note-off event (in the same track, with the same pitch number, and on the same channel...).

All of that to answer what you technically asked, but, I fear, not at all what you wanted to know.