In most contemporary songs in minor keys that I analyze and try to learn from it seems that there are no real rules as to how composers choose chords and melodies from the 3 minor scales. It seems like they just cherry pick from all 3 and create melodies with the m6, M6, m7 and M7 degrees without really taking into account ascending or descending melodies. Is there any reason to look into it any further than this or is it safe to say that the 3 minor scales are in fact one minor scale with the last 6 notes being chromatic?

-

can you show me an example where in a ascending motion there is used a minor melodic-downward scale and in the descending motion there is a minor-upward scale? – Albrecht Hügli Jan 27 '21 at 09:43

-

@AlbrechtHügli - Black Magic Woman? Or is it only from the Classical era? It did mention contemporary. – Tim Jan 27 '21 at 09:54

-

1I'm fast coming to the mindset that the defining factor of anything minor (including modes) is simply that m3. Anything else is up for grabs these days. – Tim Jan 27 '21 at 09:58

-

Which contemporary genres do you refer to? Pop? Neoclassical? You should probably add this to the question. In some traditional Scandinavian music your observation holds fairly true as well, for tunes at least a hundred years old. A well known example is Leksands skänklåt: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=V5dh2_ygfkM (written out here: http://www.folkwiki.se/Musik/4064) A more modern interpretation I like is this: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QWVQ3jCx4RI The last one even has a major third sometimes, which is fairly common in this genre as well. I think the tunes are still considered minor. – EdvinW Jan 27 '21 at 10:03

4 Answers

The are definitely not all the same and all you have to do is listen to them to hear the difference.

The natural minor scale is the same as the diatonic scale played on the 6th degree. One could argue that A minor and C major are not different scales so why bother writing songs in a minor key. The key to understanding the value in Harmonic and Melodic minor is understanding the concept of a cadence or resolution in Western music. When we write music in a major key three chords cover all the notes, the I, IV, and V or V7. A good deal of music is harmonized with just these three chords. The movement of V7 to I is very strong because you have 2 half steps resolving to chord tones in the I chord (7->8, and 4->3). This device does not exist in the natural minor scale. The chord on the 5th degree is a minor chord, there is no leading tone into the root note. The Harmonic minor fixes this by raising the 7th degree to create a leading tone to the root note. The consequence of this is to make the V chord in the minor key a Major chord. Now you have a true cadence V7-->i in the minor key. This creates a minor third (or augmented second) between the b6th and the 7th degrees which sounds cool to many ears but is not consistent with the other scales. Raising the 6th as well fixes that creating a new scale (the melodic minor) which has (1) a leading tone and (2) only contains half and whole steps.

No one "cherry picks" notes, but so what if they do! One could argue that all these "modes" just cherry pick from the chromatic scale. If you really analyze classical melodies you will see patterns in the use of melodic minor when composing the a minor key. We use the altered scale on ascending melody lines and walk down the natural minor on descending melody lines. Good examples of music do not contain random bits thrown here and there, they have well defined patterns. If one gravitates towards notes in A natural minor when in the key of C major you will get a dark minor feel but note one of a true key change. If on the other hand you use the G# (or G# and F#) when passing to the minor melody this will create a true feeling of a modulation. Whether one does this or not is a choice but there is a logic behind that choice.

In Jazz we often use what is called the Jazz melodic minor which is the ascending melodic minor played in both directions. The modes associated with this scale cover a lot of altered chords used in Jazz like X#9(b5) etc. So when soloing over Jazz changes players will often default to the melodic minor modes rather than the diatonic modes.

...without really taking into account ascending or descending melodies. Is there any reason to look into it any further

Melodic direction is part of it, but harmony is the other factor. You can find examples over and over of the raised sixth and seventh degrees used in descending lines when the harmony is dominant.

From Bach, BWV 511, in G minor...

From Handel, HWV 449, D minor...

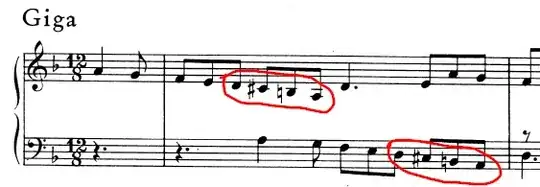

...that's from the Aria and variations, but also the Giga has two interesting passages...

...descending passage with raised sixth and seventh, but later over subdominant harmony the lowered sixth and seventh are used in an ascending passage...

...whether you want to consider D minor the tonic (red) or G minor (blue) either one uses the lowered sixth and seventh while ascending.

Nothing is difficult to understand about how this works...

- First, then the passage is scalar involving the upper tetrachord between

^5and^1the steps will usually have either both sixth and seventh raised or both sixth and seventh lowered, in other words the "harmonic minor"^5 ^♭6 ^♮7 ^1isn't commonly used. - Second, whether the sixth and seventh are lowered or raised depends on the harmony involved. Dominant uses the raised tones (otherwise you would have a cross relationship with the seventh.) Minor subdominant with use the lowered (otherwise you would have a cross relationship with the sixth.) Over a tonic chord it seems to go by the ascending/descending rule, or half-step neighbor motions below

^1and above^5. If the passage is sequential harmony it seems to either stay diatonic to the key signature or when involving secondary dominants I would expect it to used raised tones.

...is it safe to say that the 3 minor scales are in fact one minor scale with the last 6 notes being chromatic?

The main problem is conflating "scale" with "tonality" or "key." In the major/minor system there is basically one minor key tonality. In terms of scale, I think it's best to think of tetrachords. The bottom tetrachord is fixed ^1 ^2 ^♭3 ^4 but the upper tetrachord between ^5 ... ^1 is fluid with the sixth and seventh degrees variable ^5 (^♭6/♮6) (^♭7/♮7) ^1

- 53,281

- 2

- 42

- 147

The idea of 3 minor scales comes partly from the idea that a scale in western music should have seven notes, and combining that idea with the observations that

- A major dominant chord is subjectively seen to sound satisfying in minor keys (at least in some genres), 'justifying' the harmonic minor

- In some styles, raised 6th and 7th degrees in ascending motion and having those degrees lowered is seen as appropriate, 'justifying' the ascending melodic minor and descending melodic minor.

We could also note that allowing the non-flattened sixth opens the possibility of regarding the relatively common Dorian mode as minor.

Is it safe to say that the 3 minor scales are in fact one minor scale with the last 6 notes being chromatic?

All statements about what the scale of a piece, or the notes in a key, actually are are just abstractions, or models - in other words, they're simplifications that may be useful if they seem to allow you a simpler way to understand the reality of what you're seeing, and may not be useful if they are so simple they can't actually 'allow' the things you're observing in real life.

If it's easier for you to think of one minor scale with the last 6 notes being chromatic, that's fine - other people have suggested that way of looking at things.

Personally, I think I tend to de-emphasize the importance of particular scales, and prefer to think of the kind of note patterns that are common in particular styles. This is useful when looking at blues-influenced minor tonalities with bends and inflections that may not even be explicable in terms of the 9-note minor scale.

- 45,699

- 3

- 75

- 157

After some time thinking about the different minor scales, in the context of modern music with somewhat improvised melodies (ie: rock/blues), I've come to think of it this way. My understanding of this is a bit blurry at the moment, so I'm trying to write this down as best as I can.

First off, not all modern tunes are diatonic. Some of them use chord combinations that don't exist in any scale. Having said that, when it comes to minor, most songs fit one of the 3 minor modes: Aeolian (most of them), Dorian (some) and Phrygian (I don't know any examples other than in flamenco, but that's a different story).

However, everybody likes a good dominant chord: the V7 chord that resolves so well to the root. Tritone resolution theory works with major modes (by resolving one semitone up and another down), but it seems to work well with minor modes too.

So, when the song would play the v chord of a minor mode (which is strictly minor or diminished in all 3 minor modes), musicians seem to prefer using the V7 chord for a nicer tension buildup and resolution.

So, the way I see it, it's only when you're using the V chord that you use the minor harmonic, and only when improvising over the V chord that you sharpen the 7th to highlight that resolution. If you're playing in Dorian mode, sharpening the 7th gives you the minor melodic straight away. When playing in Aeolian mode, sharpening the 7th yields the minor harmonic. I'm not sure in the latter case whether musicians use the harmonic or melodic minor.

Otherwise, when soloing/improvising over the rest of the chords, you tend to use the natural minor.

- 1,299

- 7

- 13