The issue with battuta according to Fux is difficult to understand because it's not, in my opinion, explained so well by Fux. But I've been studying Baroque scores for quite a few years now, and I have a general understanding of what's going on. It helps very much to do Fux's exercises in Gradus Ad Parnassum as well as study and look over them; this clarifies so much of the text.

Quinta Battuta was not so recognized by even Zarlino, who would approach a 5th using outside in motion without issue (still, if you can close stepwise by filling in notes, this is best.)

Note: The difference between the 5th and the octave in this regard is further clarified when you start to look into some of the flavors of double counterpoint, where you define a subject and countersubject that work well and don't break rules when inverted. In double counterpoint at the 12th particularly, motion from inside out to an octave inverts to outside in to a 5th. So, notwithstanding the use of oblique motion here, you can create a nice smooth subject/countersubject relationship by using stepwise motion to expand to the octave which would give you a nice stepwise close to the 5th. If modern rules were strict about "Quinta Battuta," you would not even be able to use this type of double counterpoint.

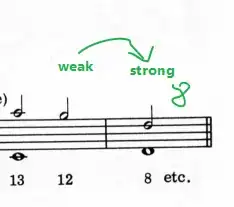

Octava Battuta is what the the masters took issue with. It really does give that beaten, slamming sound when you jump into the octave like that, which is truly best approached via oblique or inside out motion.

If you look at Fux's many examples, he never uses more than a 10th in approaching an octave in 1st species, or just whole notes. In fact, in studying the examples, you see that he actually prefers direct motion in 1st species, because then it's just a matter of correcting one of the notes in 2nd species to create inside out motion (an ideal for this interval.)

Now, again in 1st species, could you have a big leap in from say a 15th (beyond Fux's reccomendation) in one measure onto an octave in the next measure and simply correct it in 2nd species by dividing both notes?

Yes, but interestingly enough, you do not find one instance of this in any of Fux's examples. Which concludes that Fux believes that this type of motion, (i.e. the a 15th in one measure to an octave in the next) is absolutely uncorrectable measure to measure (1st species.)

But, here's the really important kicker: this rule is only in effect in 1st species.

This is crucial to understanding. Yes, you can have those crazy closes into the octave within the measure (2nd species and on,) not measure to measure.

That said, if you can make smooth voice leading within the measure you should, but when it comes to compositions with lots of voices, you will find yourself using this motion at times.